Sahel Monitoring June 2025

After a hiatus of nearly one year, this is the second entry in a new series analysing the threat environment in the Sahel region based on the terrorist propaganda output by Jama'a Nusrat ul-Islam wa al-Muslimin (JNIM), the Islamic State West Africa (ISWAP) and the Islamic States Sahel Province (ISSP), the three dominant terrorist groups in West Africa. The previous material, which analysed the situation between December 2022 and June 2024 can be found here.

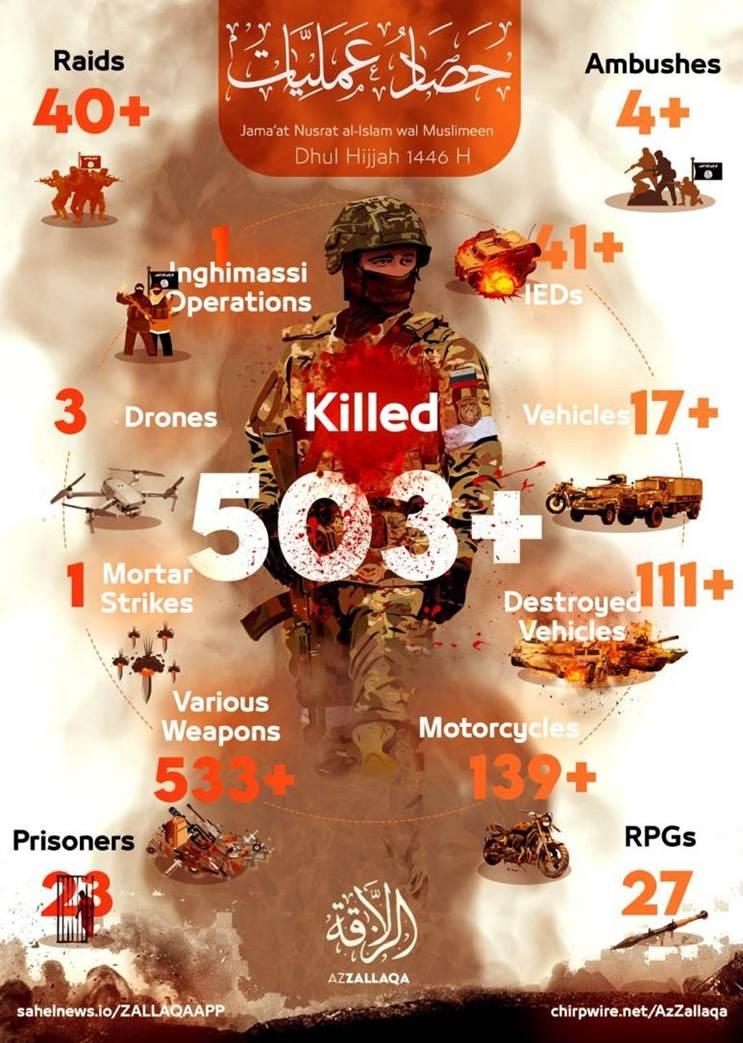

JNIM (91 claims)

June began with the Jama'a Nusrat ul-Islam wa al-Muslimin (JNIM) demonstrating its growing capabilities by coordinating complex military operations against armed forces in the Sahel. On the first day of the month, within a few hours, JNIM fighters successfully stormed two military bases on opposite sides of the Malian-Burkinabe border, one in Boulkessi (Mali) and one in Koumbri (Burkina Faso). Following their established modus operandi using rapid, lightly-armed, storming units supported by surveillance drones that assist ground operations. The terrorist fighters faced initial resistance, but they quickly overcame the defenders of both encampments. Dozens of soldiers were killed, around two dozen kidnapped, and large quantities of weapons, vehicles and ammunition were seized.

All these assaults on army barracks constitute a huge opportunity for JNIM as they allow the group to seize equipment that can be quickly redistributed across its operational territories, thereby contributing to its expansion in other areas of the Sahel, especially littoral West Africa. Additionally, war spoils represent a significant financial asset due to opportunities represented by both the local illicit weapons trade and the black market.

JNIM especially demonstrated its increased operational capabilities and self-assuredness again on June 2. On that day JNIM conducted a complex operation when a group of suicide fighters, “inghimasis,” entered Timbuktu while a mortar unit targeted a base hosting both Malian Armed Forces and Russian mercenaries of the Africa Corps while at the same time JNIM artillery shelled the military airport. Simultaneously, a handful of terrorist fighters prevented a rapid response by attacking three military checkpoints in the Northern and Eastern neighbourhoods of the city. Even though most of the assailants were neutralized, the attack demonstrates JNIM’s increasing abilities in planning and coordination.

In Benin, the coastal West African State where JNIM appears to be attempting to rapidly expand, the group officially carried out two successful attacks against an army post and a police station in the first half of June. However, there are reasons to believe the al-Qaeda branch is not claiming all its activities in the country. Between June 16-20, Islamist terrorists assaulted more military and security outposts, confirming the group’s expansion into the northern territories of Benin and its efforts to challenge the security environment to gain a stronger foothold in the country. These events were not featured in the JNIM-linked propaganda outlets.

This is not an isolated event. JNIM has repeatedly enforced a “gag order” over its activities. For this reason, it is plausible to attribute the June 12 attack on a base of the Malian military base with first person view (FPV) drones to JNIM, rather than the Azawad Liberation Front, which usually quickly claims its successful operations. One potential explanation of JNIM’s silence on these attacks could be that the terror group does not want to publicly acknowledge possessing such new technical capabilities, even though unofficial and occasional videos filmed by terrorist fighters themselves have already showcased them.

For the rest of the month, JNIM did not report additional large scale attacks, but nonetheless it continued to carry out ambushes with improvised explosive devices (IEDs) against military convoys and assaults on forward operating outposts, disrupting the supply and communication routes in the contested areas.

ISWAP (21 claims)

Similar to May 2025, the Islamic State West Africa Province (ISWAP) continued to storm army barracks in both Nigeria and Cameroon, almost unchallenged by the military in either country. In fact, almost 45% of the group’s attacks in these two countries for June fall under the so-called “holocaust of the camps” campaign. The results of these attacks were concerning. Dozens of vehicles were seized or destroyed and a substantial quantity of military equipment was looted. So far, the Nigerian military has shown little to no adaptive capabilities to this new phase of ISWAP’s military offensive against state defensive infrastructures.

However, it is important to highlight that this terrorist campaign remains mostly limited to the northeast of Nigeria, especially Borno and partially Yobe. In addition, the government’s anti-terrorism operations do yield some positive outcomes, especially thanks to the Nigerian air force, which enjoys uncontested airspace when dealing with terrorist organizations. Nonetheless, it is necessary for Abuja to review its supercamp strategy, implemented five years ago, because it clearly no longer delivers fruitful results. ISWAP clearly enjoys freedom of movement in the area, and its fighters are able to carry out cross-border activities. This is demonstrated by the growing threat Islamist terrorists represent in Cameroon, to the point that the Nigerian government recently floated the idea of fencing all the country’s borders to halt the spread of terrorist attacks.

ISSP (3 claims)

Despite being the less prolific Islamic State affiliate in the region, the Islamic State Sahel Province (ISSP) carried out two significant military operations with serious consequences in June. On June 4, the Islamic State confirmed via an ‘Amaq Media Agency statement that its fighters were responsible for storming a Malian military base in Tessit. The assault resulted in the destruction of 15 vehicles, the seizure of 11 more and the capture of valuable weapons and ammunition, while security sources reported that 40 soldiers have possibly been killed. For the next two weeks, the group only claimed one ambush using an improvised explosive device (IED).

However, on June 19, ISSP conducted one of its deadliest operations, claiming to have killed dozens of soldiers. ISSP demonstrated its increased tactical capabilities through this complex and coordinated attack. While a storming unit penetrated both an army base and a National Guard camp in Bani-Bangou, other terrorist fighters simultaneously attacked military barracks in Inates as a diversion before retreating into inhabited desert areas. This assault further strained the already battered morale of state forces, to the point that two companies located in the country’s West recently rebelled against their superiors, refusing to secure a convoy of trucks traveling from Burkina Faso to Niamey. Mutinies stemming from the deterioration of the security environment in the region are not entirely new, but the growing dissatisfaction among Nigerien armed forces is palpable and could represent a weak spot that the Islamic State or JNIM might exploit, leading to a spiral of insecurity that would further damage the country and the Sahelian States confronting the rising threat of Islamist terror groups.

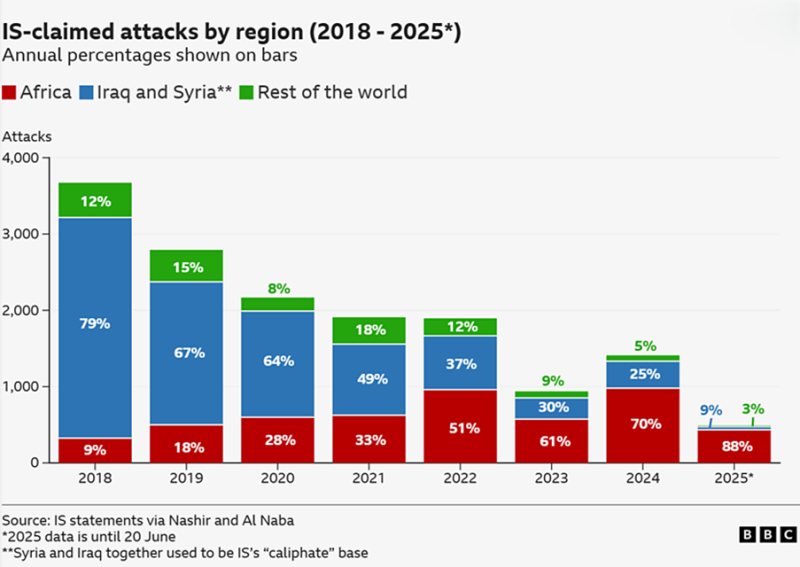

Overall, the trend in all countries affected by the Islamist terrorist threat in the wider Sahel appears worrying since national governments seem unable to cope with rising instability caused by the expanding and intensifying operations of JNIM, ISSP and ISWAP. While ISIS’s global activity has largely reduced due to the defeats it suffered in Syria and in Iraq in 2019, its African branches have increasingly expanded in terms of both attack numbers and geographical outreach. Even from a wider perspective, the situation remains unchanged: Islamic State-linked groups in Africa now “account for nearly 90% of the group’s global attack claims, up from 70% last year”.

Local authorities should develop coordination and consultation mechanisms to address the intensified violence, but no comprehensive instrument has been implemented so far. Joint partnerships remain a challenge in the region. For example, Niger has withdrawn from the Multinational Joint Task Force (MNJTF), which also includes soldiers from Nigeria, Chad, and Cameroon. An announcement made in the Diffa region stated that the country is launching Operation Nalewa Dolé in the southeast to “strengthen the security of oil fields.” This withdrawal is creating a vacuum in northern Nigeria that is being filled by ISWAP, making the borders more vulnerable.

In addition, the current political instability in several countries of the region accelerates terrorism. The military juntas of the Alliance of Sahelian States (AES) (Niger, Burkina Faso and Mali) have been accused of committing grave human rights abuses, further exacerbating the already dire situation. The overall deterioration of the security environment is also intensified by the actions for Russian mercenaries from the Africa Corps. These are more focused on self-preservation and promoting Russian interests in the region than on addressing regional security issues.

As JNIM attempts to expand southwards, Ivory Coast is implementing forward-looking measures to address the growing radicalization issue, which are working but only to a certain extent. Nonetheless, it is difficult to halt the progress that Islamist terrorist groups have already achieved. Ghana is used “as a logistical and medical rear base” by terrorist groups, while recent protests in Togo against authoritarianism could undermine political stability in the country and could shift the government’s preventive approach towards terrorism adopted so far towards a more repressive approach.

Stay up to date on our latest news.

Get the latest news on extremism and counter-extremism delivered to your inbox.