Sahel Monitoring September 2025

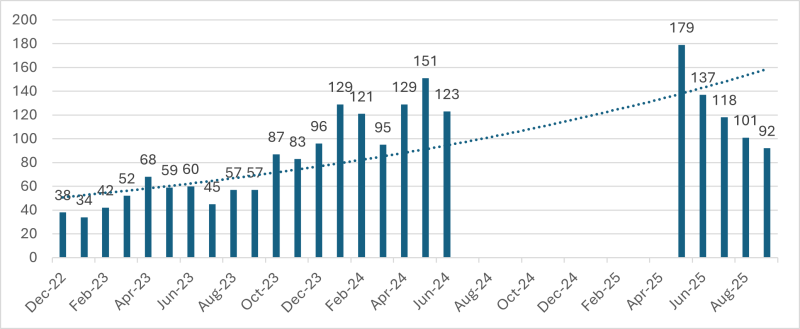

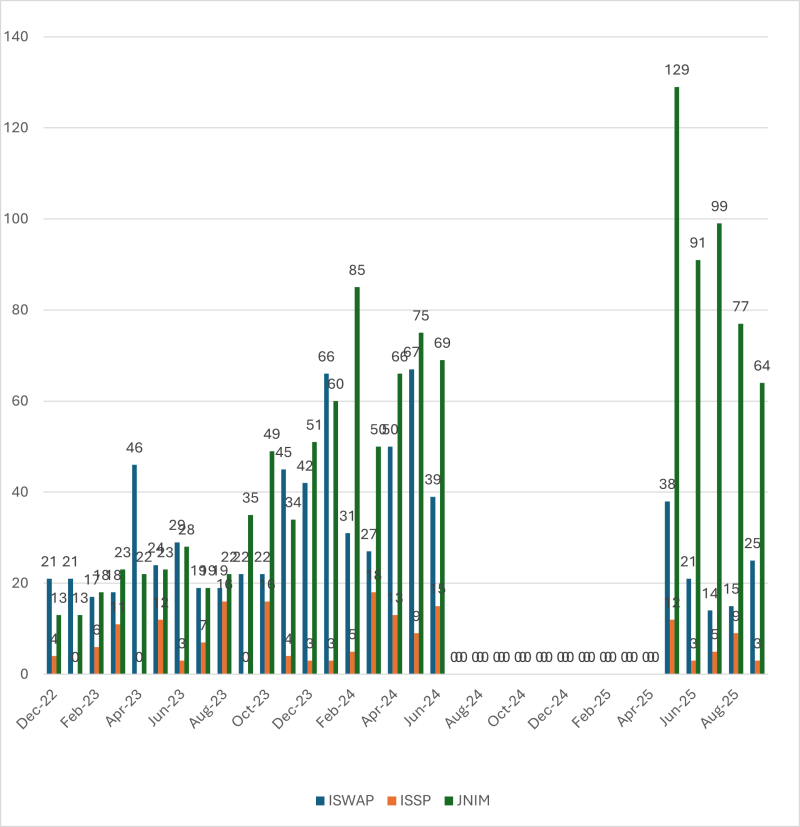

This is the fifth installment in a new series analysing the threat environment in the Sahel based on the propaganda output by Jama'a Nusrat ul-Islam wa al-Muslimin (JNIM), the Islamic State–West Africa Province (ISWAP), and the Islamic State–Sahel Province (ISSP), the three dominant terrorist groups in West Africa. Previous analyses of the threat environment in West Africa and the Sahel between December 2022 and June 2024 are available here.

JNIM (64 claims)

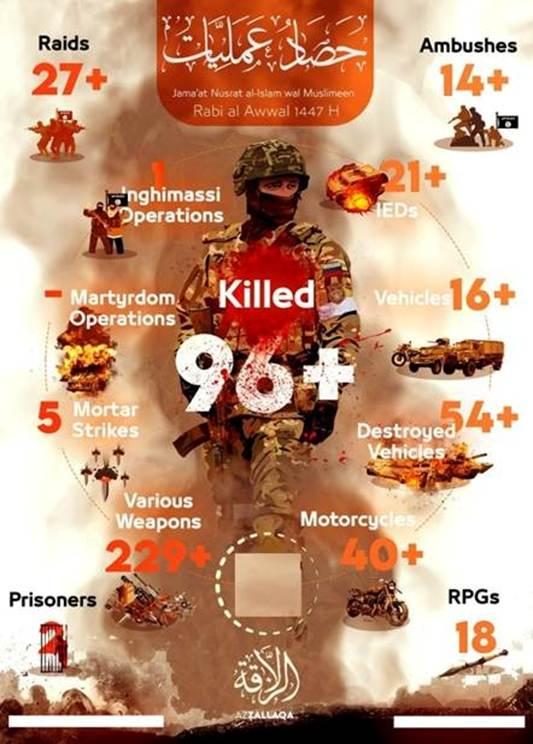

In August, JNIM issued 64 claims—34 related to Mali, 26 to Burkina Faso, and only three to Niger—alongside the usual end-of-month infographic detailing the results of the group’s military activity across the Sahel region.

Regarding Niger, the Sahelian branch of al-Qaeda carried out its attacks primarily in the second half of the month, focusing on small-scale operations. Notably, on September 27, the group claimed to have captured a Nigerien Army post in the area of Agadez, a region usually spared by JNIM activities.

In Burkina Faso, JNIM continued to operate freely, facing weak resistance from the Burkinabe military junta. Both Burkina Faso’s armed forces and the Volunteers for the Defence of the Homeland (VDP) militia have been unable to mount sufficient pressure and curtail the Islamist terrorist movement. While the military junta in Burkina Faso, led by Ibrahim Traoré, continues to consolidate its political power and pushes for illiberal measures, JNIM is steadily expanding its operations, both geographically and quantitatively. During September, the group carried out multiple attacks, especially ambushes with improvised explosive devices (IEDs) and assaults on army posts. On September 28th JNIM claimed to have carried out its deadliest operation for the month across the Sahel, allegedly killing 26 Burkinabe soldiers defending an outpost in Gomboro.

Equipment captured by JNIM in Gomboro on September 29th.

However, even when attacks result in a lower casualty toll, Islamist terrorists are usually able to seize the positions held by the Burkinabe soldiers and pro-government militants, seizing motorbikes, vehicles, light weapons, ammunition, and, sometimes, even mortars. This steady stream of equipment losses, albeit not necessarily of central importance from a conventional military perspective, represents a strategic deficit for the military junta, as it continuously strengthens JNIM’s forces with additional equipment.

Equipment captured by JNIM in Gomboro on September 12th, including 3 mortars.

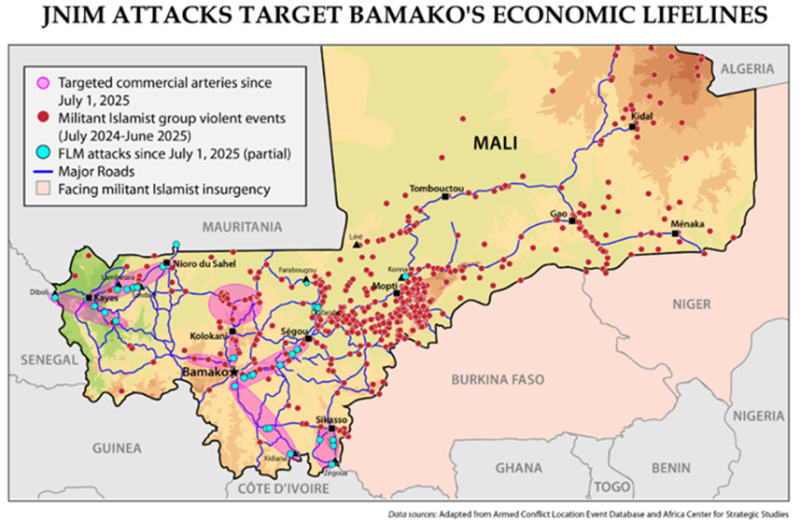

In September, Mali was the country most affected by JNIM activities. In addition to the usual attacks that also plague Burkina Faso and Niger, on September 3, group spokesman Abu Hamza al-Bambari (also known as Nabi Diarra,) announced through unofficial, low-quality footage (published on what seems to be a semi-offcial media channel called Qanaa al-Fath or the Victory Channel) that from that day onwards, JNIM would halt all transport and fuel trucks bringing vital supplies into Mali from Senegal and Mauritania.

Screenshot from the Abu Hamza al-Bambari’s September 3rd footage.

The blockade, meticulously implemented since the announcement, proved extremely effective. During the ensuing weeks, the number of oil tankers ambushed and later set on fire became a serious issue for the Malian military junta, as lack of fuel began to threaten not just the capital, but also Mopti region.

The Malian army was tasked with defending the most trafficked supply routes and escorting the trucks bringing in the vital supply of fuel. However, although this new operation was set in motion quickly, it failed to yield the expected results, as Islamist terorists continued to carry out their ambushes almost undisturbed. Additionally, this military redeployment withdrew soldiers from already-battered areas elsewhere in the country, once again forcing authorities to adapt to the new status quo and devise a strategy to end the blockade.

The junta seems to be in a difficult position: for, in the past months, it increasingly lost control of multiple regions as both separatist forces which are part of the Azawad Liberation Front (FLA) – and Islamist terrorists upped the ante by increasing their rate and lethality of attacks. This is also due to Islamist terrorists’ deployment of new tools, such as monitoring drones and first person view (FPV) drones. The forces loyal to the junta seem under equipped and unprepared to secure its vital routes while JNIM continuous its assaults on a daily basis, slowly choking the country. Both the population and the industrial sector increasingly feel the pressure as fuel prices mount.

However, this move does not come out of the blue: its origins can be traced back to JNIM’s announcement of a blockade imposed this past summer on Nioro du Sahel and Kayes (mentioned in the July issue).

Source: https://africacenter.org/spotlight/jnim-attacks-western-mali-sahel/

Apart from unofficial footage and audio clips intended for domestic audiences, in September a new JNIM propaganda outlet emerged that is dedicated to attacks in Southern and Western Mali. Named Chaine al-Fath (Victory/Conquest channel), this platform has disseminated footage of specific attacks (such as the kidnapping of three foreigners—two Emiratis and one Iranian—in Dialakoroba in late September) and messages addressed directly to the local population. The absence of clear links to the group’s official outlet, az-Zallaqa, and the difficulty in accessing the original source complicate efforts to understand the rationale behind Chaine al-Fath's creation. The channel seemingly avoids Telegram and Facebook, preferring to release content exclusively via WhatsApp.

Screenshot from one of the first footages released by JNIM through the Chaine al-Fath outlet.

JNIM infographic detailing the results of the group’s attacks for the month of September 2025.

ISSP (4 claims)

The Islamic State–Sahel Province (ISSP) has been less active, releasing merely four claims in September. In Niger, the group’s most successful operation of the month took place in Tillabéri. On September 10, its fighters entered the city and ambushed a Nigerien army convoy, killing multiple soldiers. However, for the first time since early June 2025, the group carried out military operations in the Diffa region, an area bordering both Nigeria and Chad, where Islamist terrorists and anti-junta militias have already capitalized on the lack of effective border controls. Niger recently strengthened bilateral relations with Chad, with a specific focus on boosting security ties. However, this two-party agreement only partially solves the challenges of transborder criminal and Islamist terrorist networks. Unfortunately, Niger’s participation in a wide and multilateral organization continuous to seem politically unacceptable. Abdourahamane Tchiani, who heads the military junta in Niamey, has followed the isolationist tendencies of the two other Sahelian military juntas in Mali and Burkina Faso. In late March 2025, Niger chose to withdraw from the Multinational Joint Task Force (MNJTF), an African States-run organization mandated to counter Boko Haram and other terrorist groups.

In Burkina Faso, the ISSP continues to fight JNIM, its Islamist terrorist rival in the country, as they continue to struggle for access to resources and spheres of influence. Previous Sahel Monitoring blog posts highlighted repeatedly the ongoing rift between the two organizations. Specifically, clashes between the two in Sebba, in Yagha province on September 16th, resulted in the deaths of dozens of JNIM members, as claimed by the ISSP.

ISWAP (22 claims)

ISWAP claimed 21 attacks in Nigeria and a single attack in Cameroon in September.

While the rainy season slowed down ISWAP’s large-scale assaults on military camps, the terrorists continued to conduct ambushes and IED attacks targeting soldiers, the Civilian Joint Task Force (CJTF), and civilians.

In one notable incident on September 6, ISWAP ambushed a military-protected convoy on the Gubio–Damasak road. The convoy was first targeted with an IED before the ambush fully unfolded. The group claimed to have killed 14 soldiers in the attack, while sources close to the army stated that the troops repelled the ambush and killed 13 militants.

In another attack, ISWAP launched simultaneous assaults on military camps in Banki and Bula Yobe. As seen in a video released by the group, the militants managed to enter the camp in Banki, claiming to have killed one soldier, burned six military vehicles, and captured an extensive amount of ammunition.

As demonstrated by both the ambushes and the attacks on military camps, ISWAP utilizes increasingly complex and effective attack tactics. In ambushes, the group first uses IEDs to create a distraction, while in attacks on military camps, it simultaneously targets two camps to prevent the movement of reinforcements. This tactical methodology aims at reducing the resistance capabilities of units over time and avoids direct clashes.

While the rainy season slowed down the attacks, ISWAP announced in its weekly magazine Al-Naba’ that it had launched a “da’wah campaign” across 21 villages in Borno State. The terrorists reportedly toured villages under their influence, preaching to locals about matters of faith and “pure monotheism.”

Conclusion

The number of claims issued by JNIM declined this month, continuing the downward trend observed since July. In Mali, the group shifted its main focus, abandoning large-scale operations against military outposts in favor of primarily targeting fuel trucks coming from the western and southern borders. This is part of a wider strategy aimed at strangling the country’s economy and weakening the military junta in Bamako.

As for Burkina Faso and Niger, JNIM also did not carry out complex attacks. However, that is likely a tactical pause allowing JNIM to reorganize. This absence of complex attacks does not seem to be the result of successful counterinsurgency and counterterrorism operations by the forces loyal to the Alliance of Sahelian States (AES), which includes the three military juntas in Burkina Faso, Mali and Niger. In fact, the indiscriminate violence against unarmed civilians—due both to airstrikes against non-military targets and ethnic-based massacres carried out by national armies and pro-government militias (including Russian mercenaries)—contributes to the deterioration of the security environment and, in parallel, increasing public discontent with all three Sahelian military juntas.

The ending of the rainy season in Northern Nigeria is directly linked to ISWAP’s higher number of operations. While the group largely abstained from larger scale assaults against military barracks (with the exception of the one in Azir on September 21), the diversification of its attack patterns confirms that ISWAP continues to represent a serious threat to national authorities. The recurring use of IEDs, ambushes, and assaults on military outposts demonstrates that the group maintains its operational capacity.

ISSP, meanwhile, continued to launch attacks against both security forces and JNIM, reflecting the intense competition between the two terrorist groups for resource control and local support.

Overall, the picture unfolding in the Sahel is very bleak. Terrorist groups have preserved their attack capabilities and have been able, as the case of Mali demonstrates, to escalate without facing major risks of strategic setbacks. As Mali’s economic infrastructure and supply chains come under increasingly severe threat, the pressure to find an answer to the economic and social hardships will continue to increase. The solution cannot rest solely on military means. However, the juntas, also due to the support of Russian mercenaries, seem deaf to this issue, as they continue to prefer military confrontation over constructive negotiations leading to regional and multilateral cooperation.

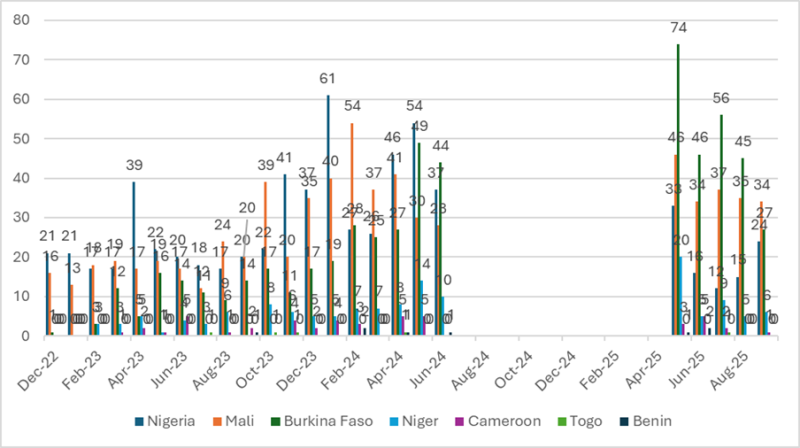

Table 1 : total number of attacks

Table 2 : attacks per group

Table 3 : attacks per country

Stay up to date on our latest news.

Get the latest news on extremism and counter-extremism delivered to your inbox.