Sahel Monitoring August 2025

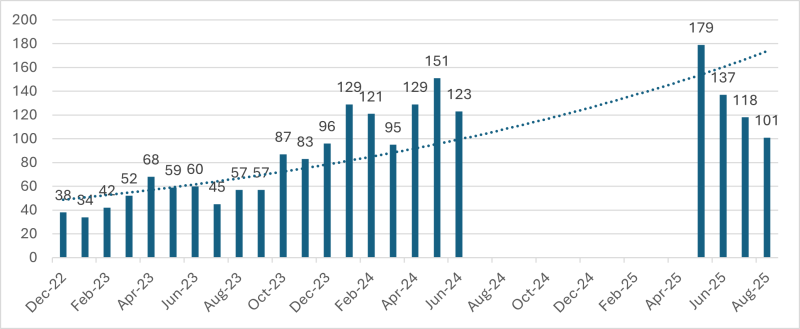

This is the fourth installment in a new series analysing the threat environment in the Sahel based on the propaganda output by Jama'a Nusrat ul-Islam wa al-Muslimin (JNIM), the Islamic State–West Africa Province (ISWAP), and the Islamic State–Sahel Province (ISSP), the three dominant terrorist groups in West Africa. Previous analyses of the threat environment in West Africa and the Sahel between December 2022 and June 2024 are available here.

JNIM (77 claims)

In August, JNIM claimed responsibility for a total of 76 attacks: 41 in Burkina Faso, 34 in Mali, and only one in Niger. The group also released an infographic detailing its operations across the entire Sahel for the month.

Overall, the rate of attacks sharply declined compared to the past months. However, the impact of these assaults has not diminished, as the al-Qaeda–affiliated group continues to undermine the economic foundations and security preconditions which the ruling military regimes of Bamako, Ouagadougou, and Niamey use to justify their authority. The security situation has deteriorated to the point that these governments have repeatedly concealed military losses and embarrassing defeats to mitigate the risk of mutinies among their armed forces and widespread civilian protests.

The security environment has eroded so much that in Niger—which has seen a relatively low number of attacks compared to its two western neighbors—the pro-government political movement M62 Union felt the need to establish an all-volunteer national unit, the Garkouwar Kassa (Shields of the Fatherland). The militia’s stated objective appears less ambitious than that of Burkina Faso’s Volunteers for the Defense of the Homeland (VDP): “not to arm civilians,” but to ensure, among other things, urban security through night patrols in order to enhance shared situational awareness. Nonetheless, the formation of the Garkouwar Kassa underscores that Niger—at the critical crossroads between Nigeria, Burkina Faso and Mali—feels increasing pressure from Islamist terror groups attempting to expand their influence within its borders.

Most countries sharing a border with Burkina Faso, Mali and Niger have been stepping up measures to deal with the expanding threat posed by the growing ambitions of Islamist terror groups. Mauritania has adopted one of the most proactive approaches, having spent the past 15 years strengthening its intelligence services and security mechanisms. Above all, however, the authorities have worked to build stronger ties with the civilian population. In 2019, they established the Mehari National Guard with the specific aim of caring for people and their livestock, building wells, and answering local grievances. This initiative, partially funded by the European Union, is set to enter a new phase in 2026. The 2026 phase marks a strategic expansion of the Mehari National Guard's footprint—strengthening security along the Malian border while deepening community-level development impacts, all under a €5 million EU-backed program.

As for Senegal, recent JNIM attacks close to the country’s border generated fears of infiltration and pushed the government to establish three new gendarmerie units tasked to patrol and secure its southwestern-most regions. While the West African states on the shores of the Atlantic have been spared Islamist terrorist attacks thus far, porous borders along the frontier with Burkina Faso represent a major weakness. Both JNIM and ISSP now threaten Togo, Benin, Ghana, and Ivory Coast. Ghana’s top priority is to rapidly end the violence in Bawku District. As Mustapha Gbande, a spokesperson for the country’s governing party, stated, “Without stability there, [there is no] hope to secure the wider northern frontier.”

Particularly, Lome and Porto Novo seem to be in the midst of a security crisis, as Islamist terrorist fighters coming from the north have carried out multiple attacks in the previous six months. Confirming this worsening trend, Togolese Foreign Minister Robert Dussey recently reported that extremists killed “at least 62 people since January 2025,” double the fatalities in all of 2023.

On August 4, JNIM released new footage from the Khalid ibn al-Walid training camp in Mali’s Sikasso region. While the group’s media agency, az-Zallaqa , recycled some clips from a previous propaganda shoot in March, the video still mattered, as JNIM stressed that its ranks are composed of a diverse mix of Islamist terrorists from various local ethnic groups, including the Diola, Bobo, Malinke, and Bambara. The group attempted to demonstrate that its ideology and goals are embraced by multiple communities. JNIM also portrayed its path as an alternative to the chaotic and violent status quo that the local population has to endure under the current military junta and their Russian allies, suggesting that the group’s approach can ease tensions among different communities.

A few frames from the Khalid ibn al-Walid training camp.

JNIM’s message can easily resonate with locals in Mali. A recent report by the American investigative nonprofit The Sentry on the role of Wagner mercenaries in Mali stressed how Russian fighters played a key role in aggravating insecurity, endangering civilians, and fragmentating the state. Charles Cater, director of investigations at The Sentry, added that the Wagner Group’s “heavy-handed and poorly informed counter-terrorism operations have strengthened alliances among armed groups challenging the State, caused substantial battlefield losses for Wagner, and resulted in higher civilian casualties.” A recent CEP report also outlined the detrimental role of these Russian mercenaries. A Le Monde report likewise confirmed the role of Wagner—later replaced by the Africa Corps—in the deterioration of the Malian security environment and in abuses against unarmed civilians. Citing the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees, the investigation highlighted that the number of people arrived in Mauritania from Mali between 2022 and 2025 has more than doubled, from 70,000 in 2022 to 160,000 in 2024. The Mauritanian government’s estimate for arrivals in 2025 is even higher, 245,000.

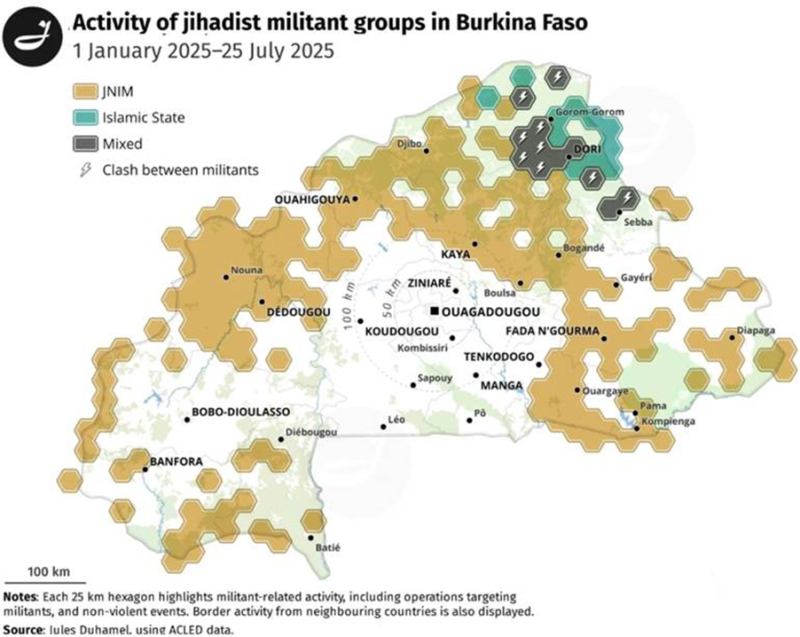

As for Burkina Faso, JNIM continues to have the upper hand, operates freely in most of the country. The group regularly storms outposts of the armed forces and VDP to seize vehicles and weapons. JNIM also carries out ambushes and IED attacks to disrupt enemy supply routes and halt the already-strained flow of regular communication between decentralized positions and larger commanding structures.

However, not all the group’s attacks have fully succeeded. Local outlets report that on August 20, as JNIM attempted to seize a military outpost in Foutouri, the Burkinabe armed forces counterattacked, reportedly killing “a large number of assailants”, including two relevant figures for the movement—Abdoul Badre, a recruiter and ideologue, and Abou Suleymane, a skilled strategist. Setbacks like this are frequent, as JNIM’s hit-and-run strategy carries risks.

https://www.julesduhamel.com/burkina-faso-conflict-map-2025-jnim-islamic-state-activity/

To counter the growth of domestic violence and prevent the risk of spillovers, the three Sahelian military juntas should increase their cooperation with African and international organizations to find reliable counterterrorism and stabilization partners. However, such expanded cooperation is unlikely, as the juntas’ isolationist policies, aimed at separation from the international community, keep moving forward. In late July, ECOWAS expelled Mali, Niger, and Burkina Faso’s officials after their governments did not reverse their decision to withdraw from the organization last January. Additionally, Ouagadougou forced United Nations Resident Coordinator Carol Bernardine Flore-Smereczniak to leave the country after she published a report on children involved in the Islamist terrorist–driven insurgency. Bamako, too, was confrontational—in mid-August, it detained a French Directorate General for External Security (DGSE) agent over espionage charges—exacerbating the already-strained relations with France. Additionally, Assimi Goïta, the current ruler of Mali, launched a sweeping arrest campaign against suspected conspirators. These developments have destabilized the country further, leaving officials and institutions in a deepening state of uncertainty.

ISSP (9 claims)

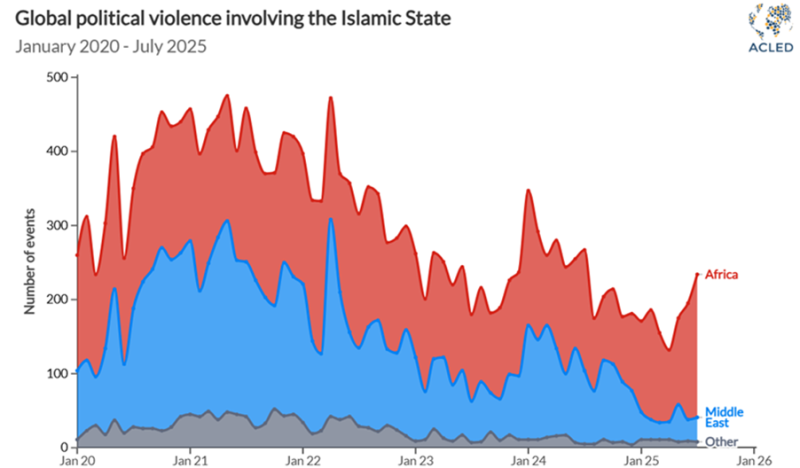

As UN Under-Secretary-General for Counter-Terrorism Vladimir Voronkov stated during a recent Security Council meeting on ISIS’s activities, “Africa is now the epicenter of jihadist violence, with unprecedented intensity in the Sahel and West Africa,” and "the threat posed by Daesh [ISIS] remains volatile and complex.”

https://acleddata.com/qa/qa-islamic-states-pivot-africa

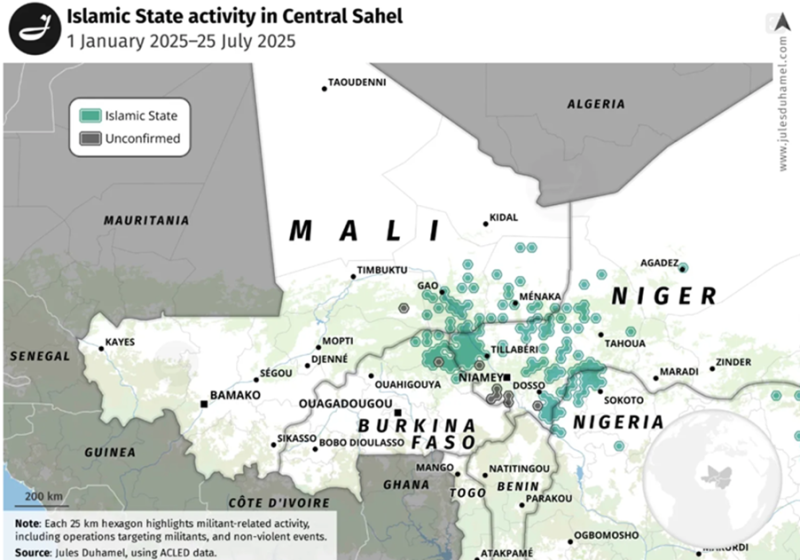

This month, Islamic State—Sahel Province (ISSP) launched attacks in Mali, Niger, and Burkina Faso. Notably, Burkina Faso was the only country where the group intensified its activity not only against the national armed forces and the central government’s allied militias but also against JNIM. In fact, over 4 military operations in the country resulted in the killing of more than 15 rival jihadists.

As previous Sahel Monitoring blog posts stressed, ISSP and JNIM are competing for influence and access to resources—especially in the Liptako-Gourma region, where the three aforementioned countries intersect. Taking advantage of the porous borders in the area and leveraging local grievances due to the abuses of the national armed forces, the two terrorist organizations are increasingly expanding southward, towards Benin and Togo.

https://www.julesduhamel.com/central-sahel-map-of-islamic-state-activity-january-july-2025/

ISWAP (20 claims)

ISWAP claimed 20 attacks in August, all of them in Nigeria. This is a slight increase from the 12 attacks reported the previous month.

The August attacks included a rise in ambushes, as frontal assaults on military bases require larger numbers of fighters, and large-scale movements are hindered by difficult terrain during the rainy season. Of the 20 documented attacks, nine involved clashes, ambushes, or improvised explosive devices (IEDs) targeting the Nigerian Army and local Civilian Joint Task Force (CJTF) militias.

A notable incident was the ambush of a Nigerian Army convoy departing from the Wulgo military camp, resulting in 10 casualties. ISWAP’s weekly publication al-Naba reported that the army enters the camp in the morning and leaves in the evening, indicating that the threat of large-scale night raids against military camps remains significant even deep into the rainy season.

Image released by al-Naba showing one of the destroyed vehicles following the Wulgo ambush.

Of the 20 attacks in August, three were frontal assaults on military camps. The attack on Kumshe was successfully repelled, with ISWAP suffering significant losses. However, the attack on Rann was devastating: the Nigerian Army lost four soldiers, three vehicles, six motorcycles, and large quantities of weapons and ammunition.

Image from Amaq News Agency showing the aftermath of the ISWAP attack on Rann.

As discussed earlier, the rainy season has made it much harder for ISWAP to conduct frontal assaults on military camps, slowing down—if not halting—the “Burn the Camps” offensive. However, this shift has allowed ISWAP to redirect resources toward disrupting Nigerian Army movements by using of IEDs and ambushes.

ISWAP also targeted softer CJTF positions across Borno State—positions less fortified than Nigerian Army camps. On August 20, ISWAP attacked CJTF positions in Mandararigau, near Biu, killing two militiamen and capturing 14 motorcycles along with other equipment.

Image from Amaq News Agency shows the war spoils captured by ISWAP in Mandararigau.

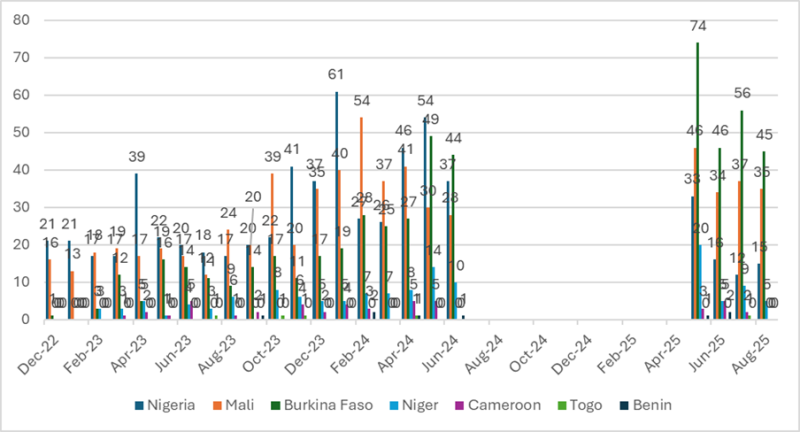

Total number of claims

Claims per group

Claims per country

Stay up to date on our latest news.

Get the latest news on extremism and counter-extremism delivered to your inbox.