Al-Qassam Brigades Propaganda: Evolution Since October 7 — Dissemination

By Sean McCafferty, EU GLOCTER PhD Fellow, Seconded to CEP

This is the second entry in a three-part blog series discussing the evolution of al-Qassam Brigades’ content, dissemination strategies, and the policy implications for combating terrorist content online.

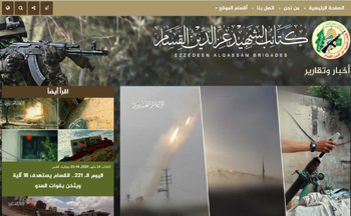

The al-Qassam Brigades (AQB) have long maintained an effective online propaganda apparatus. Following crackdowns on mainstream platforms like Twitter (X), Facebook, and YouTube, the group pivoted to self-hosted websites (Figure 1), dedicated apps (Figure 2), and a network of official and unofficial Telegram channels. AQB’s Telegram presence was established in 2015 and remains critical to the group’s sharing of propaganda to a wide audience. This infrastructure focused on exploiting self-hosting content and the inconsistent moderation practices of key platforms such as Telegram. This dissemination approach has been established over years, becoming the backbone of AQB’s surge in propaganda content during and following the October 7 attacks.

Dissemination Patterns Post October 7

Despite the somewhat increased online counterterrorism pressure, AQB have not meaningfully adapted their dissemination tactics since the October 7 attacks. Two years on from the attacks they maintain their presence in the same key online spaces and share their content in the same way. Telegram, their own websites and their app are the crucial spaces as well as a wide network of supportive channels not clearly operated directly by AQB. This continued reliance on a narrow set of platforms contrasts sharply with the received wisdom of an online terrorist network under pressure, in which we often see experimentation with new platforms and migration to fringe spaces as a response to disruption. This suggests that the group has not faced effective efforts to disrupt their dissemination of content.

However, the al-Qassam Brigades have faced some cases of disruption to their online dissemination spaces. In the immediate aftermath of the October 7 attacks there was significant disruption to their central website as the result of a distributed denial of service (DDoS) attack. Telegram also removed some Telegram channels associated with the group, however removals have been inconsistent and ineffective. In October 2023, likely due to a request from Google, Telegram blocked access to AQB Telegram channels for Android users.

Access to known AQB Telegram channels has also been restricted for users in certain geographical areas banned due to local laws. However, restrictions such as geo-blocking or through the app store are simply sidestepped through virtual private networks (VPN’s) or free and open-source software (FOSS) versions of the app. AQB themselves have shared a guide on their website of how to access their content despite disruption to their Telegram presence (Figure 2). In response to the inconsistent removal of channels AQB has reconstituted its network of Telegram channels with four prolific live channels featuring 144,792 subscribers at the time of writing. It is worth noting that in October 2025, the AQB website was briefly inaccessible with a Cloudflare ‘error 30004’ stating that the website was being updated. The website appears to have been inaccessible between the 25th of September and the 8th of October. Although attribution is unclear this disruption is likely linked to the anniversary of the 7th of October attacks.

AQB content has also been shared by regional allies’ media networks—prominently through Hezbollah’s websites and Telegram channels. Hezbollah’s channels have faced even less disruption than AQB channels, despite having been designated by several countries with proactive online CT regulation, such as the US, UK, and EU. The EU makes a distinction between the military and political wings of Hezbollah, complicating the identification and removal of Hezbollah content. As a result, AQB content has continued to be shared by Hezbollah channels even when AQB’s own channels have faced disruption.

The content has also been shared through a broader network of supporter or sympathetic channels not directly operated by the group or other terrorist organisations. These supporter channels operate as a decentralized network of pro-Hamas accounts on mainstream and fringe platforms. There, content is repurposed, and attack footage, statements, and narratives are spread. This looser network acts as a force multiplier, ensuring content reaches audiences even if official channels are disrupted. Further, this looser network repackages AQB content and narratives and shares them.

Since October 7, new Telegram channels have emerged as aggregators, framing AQB propaganda alongside Palestinian Islamic Jihad (PIJ) content within a broader regional narrative, linking the conflict to Hezbollah, the Houthi, pro-Iranian militias in Iraq, and the Islamic Republic Revolutionary Guard Corps (IRGC). This framing not only amplifies reach but also embeds AQB messaging within a wider “axis of resistance” narrative, making it more resilient to platform moderation as it becomes less overly branded with the symbol of the AQB and more appealing to a broader audience.

Death of Abu Obeida

Abu Ubeida was a central figure in shaping AQB narratives, regularly delivering statements that framed the group’s military actions, justified its strategies, and sought to rally both domestic and international support (Figure 3).

The Israeli Defence Forces (IDF) killed him on August 30, 2025. His death has disrupted AQB’s ability to maintain a consistent and authoritative voice. Abu Ubeida and his statements were central to the dissemination of AQB content. A section on the AQB website and several Telegram channels are dedicated solely to his statements. The spokesperson sections of the website and Telegram channels remain dormant since the end of August 2025, likely due to Abu Ubeida’s death. Nonetheless, AQB propaganda has continued to be shared prolifically since then, calling into question whether his killing will significantly disrupt propaganda dissemination.

Lack of adaptation

The stagnation in AQB dissemination tactics is striking. Particularly in comparison to the significant evolution of the propaganda content itself during the past two years. Unlike other terrorist groups such as ISIS, which has repeatedly experimented with new platforms despite the relative stability of their own core online spaces, the AQB have shown little desire to innovate. This may be due to several key factors. Hamas's status as a pseudo-state in some countries and designations as a terrorist group in others, has created jurisdictional loopholes in which the group’s content is not legally considered terrorist has resulted in less aggressive moderation compared to groups that have broader international consensus such as ISIS or al-Qaeda. Telegram’s initial reluctance to remove AQB channels, citing concerns over “destroying a source of information,” highlights the challenges of cooperating with tech platforms. Terrorist-operated websites, and self-run apps are often hosted in jurisdictions with inconsistent or no enforcement; these have proven difficult to disrupt long-term despite concerted efforts.

Conclusion

The sustained availability of AQB content and the striking lack of adaptation suggests that current online counterterrorism measures are not sufficiently pressuring the group to change their tactics. AQB online propaganda continues to be disseminated without consistent disruption on Telegram, as well as through their primary website and dedicated app. These two self-hosted spaces currently remain beyond the reach of existing online counterterrorism (CT) measures. Further, significant losses of key leadership figures, prominently the death of Abu Ubeida, AQB’s central propagandist and spokesperson, has not significantly changed the dissemination of AQB propaganda aside from ending his regular statements and speeches, which are yet to be replaced at the time of writing. The next blog in this series will explore how these findings can inform potential reforms of EU measures such as the Terrorist Content Online Regulation (TCO) and the Digital Services Act (DSA) with the goal of fostering a more effective approach to online counterterrorism. This blog entry will also include several concrete policy recommendations for governments and tech platforms.

Stay up to date on our latest news.

Get the latest news on extremism and counter-extremism delivered to your inbox.