Al-Qassam Brigades Propaganda: Evolution Since October 7 — Content

By Sean McCafferty, EU GLOCTER PhD Fellow, Seconded to CEP

This is the first entry in a three-part blog series discussing the evolution of al-Qassam Brigades’ content, dissemination strategies, and the relevant policy implications for combating terrorist content online.

Two years ago this week, al-Qassam Brigades (AQB), the military wing of Hamas, led the October 7, 2023 terrorist attack on Israel and Israeli civilians, in which an estimated 1,200 Israelis and other nationals were killed and 251 taken hostage. Since then, AQB have launched ongoing rocket attacks and engaged in urban warfare against the IDF following Israeli offensives in Gaza. As of writing, the United Nations reports that the conflict has resulted in an estimated 64,000 Palestinian deaths, based on data mainly supplied by the Hamas-controlled Ministry of Health in Gaza. In January 2025 the Israeli Defence Forces (IDF) reported 891 IDF soldiers killed since Oct 7, 2023.

The unprecedented scale of violence on October 7, 2023, and the ensuing devastation in Gaza have had deep repercussions both online and off. The conflict has led to extreme suffering in Israel and in the Palestinian territories as well as a global rise in incidences of antisemitism and islamophobia. This blog post focuses narrowly on how AQB’s propaganda has evolved in the two years since the attacks: despite the loss of its key leaders to Israeli airstrikes and assassinations, AQB has continued producing propaganda throughout the conflict.

Several key changes to the al-Qassam Brigades propaganda content have been observed across the last two years. Three categories of the key changes will be addressed here. Firstly, several of these are innovations shaped by the nature of the conflict, such as videos showing AQB fighters attacking IDF troops inside Gaza and images of so-called fallen ‘martyrs’. Secondly, content has been shaped by the long consequences of the October 7 attacks such as hostage-related propaganda. Finally, the content has also been shaped by much larger technological changes such as the incorporation of generative AI imagery in propaganda output.

Conflict Footage

On July 5, 2025, the AQB posted a video of an ambush on IDF troops in Khan Yunis (Figure 1). This video contains the key elements in the conflict footage shared by the group post-October 7. Following the Israeli military campaign in Gaza the primary AQB narrative shifted from glorification of the October 7 attacks to AQB rocket attacks on Israel and ambushes on IDF forces in Gaza as so-called “resistance” to an invading force.

Figure 1. al-Qassam Brigade video of an ambush in Khan Yunis | Source: Telegram

This video and many others are either filmed from static cameras set to capture the attack or prominently from cameras or phones mounted on the attack perpetrator giving the viewer the attacker’s perspective. These perpetrator perspectives have become common not just in AQB content but across a wide variety of terrorist propaganda and even the content of military forces. This is only one example of hundreds of similar videos of ambushes, rocket, and sniper attacks on IDF troops. This content is widely shared to glorify the attacks. The pivot to perpetrator-generated footage and the prioritisation of staged ambush footage in the overall propaganda output is a significant change to AQB’s content and primarily due to the change nature of the conflict with the IDF since the end of 2023.

Figure 2. al-Qassam Brigade video | Source: Telegram

This is unsurprising given the urban warfare against the IDF. However, some other elements are unique and deliberate innovations. For example, the AQB have incorporated significant gamification elements (deliberate incorporation of game-design elements to make content more engaging, accessible and shareable) including highlighting the targets of attacks with overlayed flashing and the now emblematic red triangle. The incorporation of these gamification elements has developed a distinct visual iconography for the conflict, which has become a recognisable part of the AQB branding. This symbolism is widely shared and amplified by supporters online, further embedding its association with the groups messaging and tactics.

Hostage Content

On October 7, 2023, 251 hostages were taken into Gaza. Since then, hostage welfare, responsibility for their captivity, the risk of death, and prospects for release have become central and highly contentious issues in the conflict and are reflected in the AQB as well as the wider Hamas propaganda output.

Hamas regularly issues threats and ultimatums, warning that hostages’ lives are at risk due to Israeli military operations or refusal to negotiate. Their propaganda places all blame for any harm to the hostages on Israel. Crucially, these threats are often shared in both Hebrew and Arabic, indicating an intent to reach an Israeli audience (Figure 3). Hamas has sought to exchange hostages for Palestinian prisoners in Israel and the withdrawal of Israeli troops from Gaza.

Figure 3. al-Qassam Brigade poster | Source: al-Qassam Brigade website

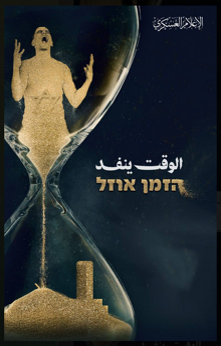

On August 2, 2025, a video featuring hostage Evyatar David showed him digging his own grave, staged propaganda imagery that is reminiscent of hostage footage first made infamous by ISIS in Syria and Iraq. On September 23, another video featured Alon Ohel blaming Netanyahu for his continued captivity. Both ended with the phrase “Time is Running Out” beside a draining hourglass. In each case, the hostages themselves were used to reframe their captivity as solely the result of Israeli actions rather than those of the AQB.

Simultaneously and contradicting these threats, AQB propaganda also attempts to show hostages being treated well. These portrayals aim to counter abuse allegations and depict the group as humane and responsible, despite extensive contradictory evidence, including subsequent images and footage of hostages.

Hostage handovers have been carefully staged to demonstrate organisational resilience despite heavy losses from Israeli airstrikes and the killing of key leaders. During the January 25, 2025 handover of Karina Ariev, Daniella Gilboa, Naama Levy, and Liri Albag to the International Committee for the Red Cross (ICRC), AQB fighters appeared in large numbers, displaying pristine uniforms and weapons to suggest sustained capacity. The hostages were released smiling, wearing ID lanyards, and carrying certificates and gift bags. The framing of this handover attempted to portray Hamas as merciful, organised and with a sustained military capability.

Figure 4. Images from the release of Karina Ariev, Daniella Gilboa, Naama Levy and Liri Albag | Source: Telegram

AQB use of hostages has become central to their propaganda strategy. Videos, threats, and choreographed handovers serve multiple aims: pressuring the Israeli public and government, shaping international perception, and seeking legitimacy. By portraying hostages alternately as victims of Israeli policy and as well-treated detainees, Hamas attempts to control the narrative. However, this contradictory messaging, shifting between threats of execution and displays of apparent humane treatment, ultimately highlights the instrumentalisation of hostages as tools of negotiation and propaganda.

Incorporation of generative AI

AI tools have been incorporated into the production of content by the AQB media wing and broader network of supporter-created content. While it is difficult to ascertain the backend of this process, it is likely that the group and its supporters are using generative AI tools such as ChatGPT, Character.ai, Dall-E, Gemini / Bard, Midjourney to augment their visual propaganda. This is most apparent in the AQB’s posters and propaganda images, which often contain generative AI components. When checked using AI detection software several posters were identified as likely AI generated (Figure 5). AI images have been used across the two previous categories with generated images displaying hostages and fighting in Gaza. The use of these AI images may be in place to augment the quantity of real footage and images, to simplify the content production process, or to make the content more palatable to audiences compared to the disturbing violence on show in real images of the conflict.

Figure 5. AQB posters containing generative AI components. Source: al-Qassam Brigade website

Conclusion

Over the past two years, the al-Qassam Brigades have adapted their propaganda to reflect the evolving realities of the conflict, frame the narrative of the continued captivity of hostages as an instrument of propaganda and negotiations, and exploit new technological tools. From combat footage filmed with gamified visuals, to hostage videos framing captivity as Israel’s fault, to the use of generative AI, AQB content has evolved across the last two years. Their shared trait is an attempt to display the resilience of the group in the face of major losses.

Stay up to date on our latest news.

Get the latest news on extremism and counter-extremism delivered to your inbox.