This report is part of a multi-year study of ISIS’s ongoing insurgency in central Syria, which includes monthly updates and deep dives into specific events, such as: ISIS financial operations, the September 2021 attack in Damascus, ISIS media changes in the Badia, the April 2021 mass kidnapping in Hama, and tribal dynamics in the insurgency and the regime’s response.

The last time Ali Ahmed’s family saw him was in a 13 second video where the young boy states his name, the day’s date, and claims that he is okay. The video was sent to Ali’s father by his kidnappers on March 6 as part of a ransom negotiation. Three days earlier, Ali and four other young teenagers were tending to their sheep in the desert of western Deir Ez Zor when armed men in a truck and on motorcycles attacked them, seizing four of the children and wounding the fifth, who escaped despite being shot. The kidnappers then contacted the children’s parents, the sheikh of the Busaraya tribe from which the boys hailed, and several local officials, demanding $20,000, food, and fuel in exchange for each of the boys. The community agreed immediately, but when asked for proof of life, the attackers began to stall. First, they sent the video of Ali, then claimed they had killed the other three children. When asked for pictures of the bodies, the attackers said the boys had already been buried. When pressed further, the attackers said that the boys had been relocated “somewhere far away.”

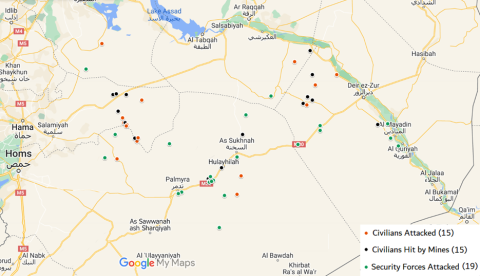

This attack is just one of nearly 50 targeting civilians across central Syria since February, leaving hundreds dead, wounded, or missing. Many of the attacks occurred while locals ventured onto the desert plains in search of truffles, an expensive delicacy that sprouts following the winter rains. Other attacks have targeted shepherds, while some people are simply shot or killed by mines while driving down country roads. The dangerous lives of central Syria’s villagers generated international headlines in February when a group of nearly 170 truffle pickers were ambushed in the southeast Homs desert. Their small security escort and as many as 60 of the pickers were gunned down and dozens were wounded as they fled on foot across the plains in search of a nearby army outpost. Many Syrian opposition outlets were quick to blame “Iranian militias” rather than ISIS, citing past atrocities committed by Syrian Shia militias and Iranian-commanded foreign fighters against Sunni civilians. Yet much of the discussion around this issue ignores the continued precarious role Badia locals play in the cat and mouse game between Syrian security forces and ISIS, and the years of attacks on locals preceding February’s brutal events, all of which are deeply rooted in the hyper-local aspects of ISIS’s five-year insurgency.

Between ISIS and Assad

Locals play a complicated and dangerous role in the years long battle for central Syria. Both regime forces and ISIS cells rely on sympathetic locals for information on enemy movements. Shepherds and farmers traverse the countryside beyond their villages every day, making them ideal observers of any suspicious activity. Regime forces rely on them to report when unknown or suspicious vehicles and people cross the plains while ISIS sympathizers share intelligence on regime patrols and mine fields with local militants. ISIS cells also rely on local trade to sustain themselves with basic goods. Due to the actions of a few individuals, entire communities are suspected by both regime security forces and ISIS of aiding the other, increasing tensions and raising the risks of attacks.

Meanwhile, destitute economic conditions have pushed many men to join local pro-regime militias. Chief among them are the National Defense Forces (NDF) and Liwa al-Quds, both of which draw heavily from locals in their respective areas, mirroring their own military and recruitment structures on the local tribal milieu. Some communities have been affiliated with the NDF since the rise of ISIS in 2014, while other men have joined in more recent years after reconciling with the regime. The economic crisis has also driven men and women to venture deeper into the desert every year in search of truffles to supplement their meager wages, while the years-long drought has negatively impacted the available grazing areas for shepherds. Sheep grazing and truffle hunting thus push civilians farther into no-man’s land every year, outside the protection of security forces and close to territory controlled by ISIS. Both sheep and truffles are also key economic commodities for roving ISIS cells, putting militants and locals in competition with each other, further endangering civilians.

The Busaraya Case Study

The political affiliations of the Busaraya tribe are a prime example of the complex relationships that impact security in central Syria. According to one of Ali’s relatives, the Syrian regime authorities in Deir Ez Zor City refused to help the tribe following the kidnappings, instead telling the families they should just pay the ransom for whoever is still alive. Six days after Ali’s kidnapping, 12 more Busaraya men were kidnapped by unknown attackers while picking truffles in the nearby desert. Their dead bodies were found two weeks later. On March 19, another group was attacked in the same area, with two killed and four more kidnapped. Still, the army offered no help.

Historically concentrated along the strategically important belt of towns stretching from Deir Ez Zor City north to Ma’adan, in Raqqa, and west along the Deir Ez-Zor-Damascus highway to Shoula, the Busaraya tribe has fought ISIS since they first began taking over eastern Syria in 2014. While the tribe’s members were split between opposition factions and pro-regime groups in the first years of the Syrian Civil War, the rise of al-Nusra Front and then ISIS in Deir Ez Zor led the Free Syrian Army (FSA)-affiliated members to either leave for northwest Syria or join the regime’s National Defense Forces (NDF) in order to continue the fight against ISIS. This author spoke with multiple Busaraya members living in west Deir Ez Zor in March, all of whom described their community’s political allegiances as firmly anti-Iran and anti-ISIS above all else.

Those interviewed spoke at length about their resentment of Iranian efforts at conversion, and several accused Iranian-backed militias of drug smuggling and abuses against civilians. They also view the Syrian army and local authorities in Deir Ez Zor City with disdain, frequently claiming that the army refuses to protect them or support them with arms and soldiers after they are attacked. Their loyalties are framed specifically around their tribe and community, citing the efforts their political and security leadership has made over the years to protect the towns from both Iran and ISIS. All those interviewed spoke fondly of the pro-regime NDF and Liwa al-Quds factions in western Deir Ez Zor, which are drawn directly from local men and whose commanders hail from the area. It is NDF and Liwa al-Quds fighters who patrol the deserts and mountains of west Deir Ez Zor, accompany truffle pickers, and respond to attacks against civilians. In 2020 and early 2021, these groups were mired in battles with roving ISIS cells that left dozens of militia-men dead, including the local NDF commander Nizar al-Kharfan.

The army eventually launched a major campaign across the region, slowly pushing ISIS back in 2021. Western Deir Ez Zor finally experienced calm as security returned for more than a year. All this changed in February 2023, when a string of brutal attacks and kidnappings targeting civilians began occurring across central Syria, also known as the Badia, where ISIS cells have operated an insurgency for more than five years. 200 locals have been killed, 80 wounded and as many as 47 kidnapped by unknown assailants across the Badia between mid-February and mid-April.

Years of Suffering

Civilians have been regularly targeted in central Syria long before February’s attack on truffle pickers in Homs. For example, in late 2020 and early 2021, dozens of shepherds were killed and their flocks stolen across eastern Hama, southern Raqqa, and northeast Homs governorates. Sheep theft has been a major source of income and sustenance for ISIS cells operating in the remote Badia for many years. According to a regime security officer deployed in eastern Hama in 2021, suspected ISIS militants had been stealing “hundreds” of sheep every week from locals in late 2020 and early 2021, and no locals or security forces could track them down. These sheep were often smuggled into the bordering Syrian Democratic Forces (SDF)-controlled areas of Raqqa, where they were sold at sheep markets or on the black market, according to the director of a sheep market and local SDF commanders interviewed by this author in 2021 and 2022. The sale of sheep served as a major source of income for ISIS cells, and shepherds suffered for it. Since mid-2020, there have been at least 34 reported attacks against shepherds in the Badia, many also involving the theft of sheep. The last four of these attacks occurred in the first half of March.

Civilians have also been targeted for ransom. The most prominent instance of this occurred in April 2021 when ISIS militants launched a major attack ambushing multiple civilian convoys on a remote highway in southeast Hama. The attackers killed all of the accompanying regime security forces and successfully kidnapped nearly 70 locals, quickly arranging a prisoner exchange and winning the release of dozens of detained family members of the ISIS fighters. Other kidnappings have had more murky motives. For example, in 2020 a teenage Busaraya boy was kidnapped and held for six months. He later told his family that the ISIS militants holding him gave him the choice of joining or returning home. When he chose the second option, they drove him to Deir Ez Zor City and freed him.

Other attacks have targeted oil workers as part of ISIS’s broader “War of Economic Attrition” against the regime, which has framed its Badia insurgency for years. Such attacks include the July 2020 kidnapping of a gas plant worker in southern Raqqa, the June 2021 attack on a work bus in southeast Raqqa returning from the Wadi Ubyad Oil Field, the December 2021 attack on workers and soldiers returning from the Kharrata Oil Field in Deir Ez Zor, and the December 2022 attack outside Deir Ez Zor City when ISIS fired rockets at two buses carrying workers to the Tayyem Oil Field, killing at least 10. ISIS militants have also regularly targeted security forces in and around the oil and gas fields that dot the Badia, but clearly view civilian workers in these fields as a key element of the regime’s energy infrastructure.

Long-Running Insurgency

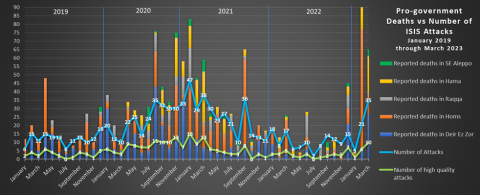

The Syrian regime and its Russian and Iranian allies captured central Syria from ISIS in the summer and fall of 2017. Yet within just a few months, ISIS remnants were conducting isolated attacks across Homs and Raqqa and engaging in large-scale battles against regime forces west of the Euphrates River. The group’s Badia insurgency steadily grew throughout 2018, receiving a boost in early 2019 as fighters fled the U.S.-backed Syrian Democratic Forces’ (SDF) final offensive against ISIS’s last stronghold in eastern Deir Ez Zor. ISIS activity in the Badia increased dramatically in early 2020 as cells expanded their reach into eastern Hama and southern Raqqa for the first time since 2017, and began to successfully capture large military outposts and ambush civilian and military convoys on major highways.

These attacks finally triggered widespread regime anti-ISIS operations, bolstered by Iranian ground support and Russian airpower, beginning in 2021. After months of hard fighting, these operations succeeded in pushing ISIS cells back from urban centers, highways, and key energy infrastructure. More localized operations also succeeded in completely ending ISIS small arms attacks in east Hama and nearly ending them in south Raqqa. ISIS’s Badia insurgency was thus muted from late 2021 through late 2022. Regime operations had limited ISIS’s freedom of movement in the Badia, while the security situation in northeast Syria had grown worse—and thus more favorable for ISIS operations. Meanwhile, the Coalition’s repeated targeting of top ISIS leaders and the death of the Badia Emir in 2021 left conflicting policies from ISIS leadership regarding the role of central Syria cells. All of these factors seem to have led to a shift in ISIS resources out of the Badia. Documented attacks against civilians during this period dropped significantly, were almost exclusively confined to eastern Hama, and predominantly involved mines. Locals in western Deir Ez Zor and southern Aleppo confirmed that security had drastically improved last year.

All this changed in February 2023, but the groundwork was being laid as far back as August. The July 28, 2022 edition of ISIS’s weekly al-Naba magazine contained a three-page interview with an alleged senior ISIS commander in the Badia lauding the persistence of militants, explaining the necessity of the lack of consistent ISIS media coverage of their attacks, and once again asserting the insurgency’s role within the “war of attrition” against the regime. The interview heralded a new wave of ISIS attack claims in central Syria following a year of near total silence from official ISIS outlets. Through the rest of the year, ISIS regularly published text and photos of attacks against regime security forces in the Badia, while locally reported ISIS activity steadily climbed in quantity and severity. Separately, an internal security forces commander from the rebel group Hayat Tahrir al-Sham (HTS), which rules Idlib, shared intelligence gathered from ISIS fighters in HTS custody with this author in September indicating that that regime forces had killed the ISIS Badia Emir, Abu Ali al-Iraqi, sometime in 2021 (possibly sometime around July when ISIS media from the Badia almost completely ended). This event triggered a series of conflicting orders from ISIS leadership on the role and direction of the Badia insurgency. In July 2022, ISIS leadership allegedly finalized plans for a re-organization of the Syria arena, part of which involved a re-centering of the Badia as a key battle front.

Resurgent ISIS

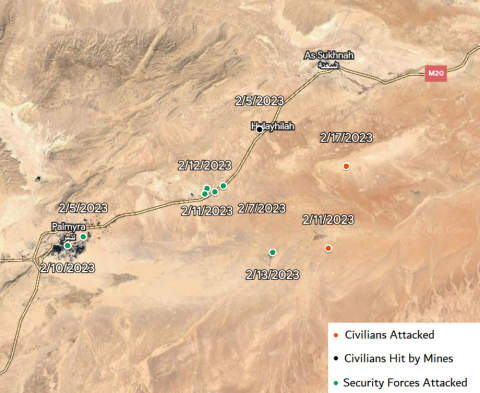

In February 2023, the steady uptick in ISIS activity that had begun six months earlier swelled into a wave of sustained attacks against both security forces and civilians across the Badia. Not mentioned in the general media coverage of the February 17 massacre of truffle pickers was the preceding week of intense battles between regime security forces and ISIS cells across eastern Homs. For example, on the night of February 7, ISIS fighters reportedly set up a checkpoint on the highway near the town of Arak, which hosts a major oil field, triggering heavy clashes with security forces. Four days later, sustained battles erupted around Arak for at least 48 hours, while other ISIS cells ambushed a group of truffle pickers east of the nearby T3 Pumping Station, killing at least four and injuring 10. On February 13, units from Russia’s Wagner PMC joined in new clashes around T3. The next day, a regime soldier was kidnapped while on patrol in the mountains north of this region.

The February 17 massacre was thus part of a broader ISIS campaign pressuring regime forces in the area. According to local security forces interviewed by this author, two ISIS cells ambushed the group of truffle pickers as they entered the Wadi Doubayat region east of Arak and northeast of T3. As one cell initiated the attack, a second reportedly moved in and ambushed fleeing civilians. Simultaneously, a third ISIS cell attempted to seize the largest Syrian army position outside Arak, though the attack failed. When security forces finally reached the site of the truffle picker attack, they found several bodies decapitated with notes pinned to them warning locals of a similar fate if they continued “to work with the regime.”

These attacks marked the end of heavy fighting in east Homs, but other ISIS cells began increasing their activity in eastern Hama. On February 14, suspected ISIS militants shot one truffle picker and kidnapped another in the countryside of southeast Hama. It was the first suspected ISIS small arms attack in the province since September 2021, marking a dangerous reversal of otherwise successful security operations in 2021 and 2022. The following two weeks, at least 17 more locals were killed and nine were wounded by gunshots and mines in the same area of east Hama. Attacks in this area continued into early March, with nearly a dozen more civilians killed and wounded and thousands of sheep stolen from local shepherds.

Attacks against truffle pickers and shepherds then spread from Homs and Hama to Deir Ez Zor, Raqqa, and Aleppo. In the first half of March, assailants in these three governorates killed another 28 civilians, wounded nearly 50, kidnapped 38, and stole more than 1,000 sheep. These attacks were largely concentrated in western Deir Ez Zor, where most inhabitants belong to the Busaraya tribe. On March 2, a truck carrying truffle pickers into the desert hit a mine, leaving six dead and 45 wounded. The next day, Ali and his friends were attacked in the western desert. Four were kidnapped while one managed to escape. Six days later, a group of truffle pickers were attacked farther west, and 12 were kidnapped. Their bodies were discovered two weeks later with gunshot wounds to the heads. On March 19, another group of Busaraya locals, this time guarded by some local Liwa al-Quds members, were again attacked in the western desert. Two civilians were killed and three were kidnapped in the initial attack as everyone fled. Busaraya-linked NDF forces quickly responded and gun battles raged for four hours. Meanwhile, to the northwest, two shepherds from the al-Buhamad tribe were attacked while in the Raqqa desert. One was killed, one was kidnapped, and 800 sheep were stolen. A few days later, 30 truffle pickers from the town of Safira were kidnapped while in the desert outside Khanasir, in southern Aleppo. According to a Safira resident who spoke with this author, this was the first attack against locals in the area in years. Attacks returned to east Hama late in the month as well. On March 18, five locals disappeared in the eastern desert, their bodies found executed only weeks later. On March 23, another five civilians, this time from the Haddadin tribe, were shot to death while truffle picking in eastern Hama.

Mystery Attackers

No group has taken responsibility for any of the attacks against civilians in central Syria—nor the less frequent but steady attacks on security forces this year. Some blame Iranian militias, some blame ISIS, and still others blame criminals. As a local in Safira told this author, referring to the 30 locals kidnapped outside Khanasir, “Who you blame depends on your political affiliations. If you support the government, you will blame ISIS, if you support the opposition, you will blame the Iranians. But the truth is that no one knows.” However, he pointed out that the Iranians have been present in southern Aleppo since 2018, yet this was the first instance of civilians being kidnapped. One Busaraya local who runs a small tribal news page on Facebook was insistent that the attacks in west Deir Ez Zor were committed by Iranians and their Afghan and Pakistani foreign fighters. “They use this desert to smuggle drugs, and there has not been ISIS here for many years,” he said. He also cited long-standing tensions between the Busaraya and Iranians, whose attempts at Shia proselytizing have been harshly rebuked by the community. However, another Busaraya local who works as a journalist took a more nuanced approach, contending that ISIS has long been present in the western desert and that no one truly knows who is responsible. As an anti-Iran NDF officer put it “This is precisely what ISIS wants, they want everyone to doubt and point fingers everywhere.”

Across the Euphrates in northeast Syria, ISIS cells have heavily utilized this strategy of uncertainty to drive a wedge between local Arabs and the SDF. Since 2019, ISIS cells have targeted local Arab sheikhs, civil society, and businessmen, primarily in eastern Deir Ez Zor but also in Raqqa City, usually without claiming responsibility for the attacks. This results in many locals accusing the SDF of being behind the attacks, citing other SDF murders of Arabs and the Kurdish administration’s authoritarian practices towards Arab political leaders. The uncertainty, fear and chaos bred by these anonymous murders has severely weakened the SDF’s ability to gain local support and root out ISIS supporters, while also making it easier for ISIS to extort and threaten locals who fear for the own lives amid the general security chaos.

It is therefore reasonable to assume ISIS would implement a similar strategy in central Syria. Of course, simpler motivations can be at play as well. As previously noted, ISIS has for years used sheep theft in the Badia to fund its insurgency, has used kidnapping for ransom and terror, and is incentivized to keep civilians out of regions where its fighters are based or use as transit. Each attack must be examined in their specific local context. The February attacks in Homs, for example, occurred both during a minor ISIS offensive against security forces in the same area and targeted civilians when they moved into the ISIS stronghold of Wadi Doubayat. The western Deir Ez Zor attacks, meanwhile, targeted a tribe that has fought ISIS since its inception and is a key pillar of local security in the region. These attacks succeeded in deepening the rift between the Busaraya and the Syrian army and state authorities, exacerbating anti-Iran animosity, and resulted in the kidnapping of more than a dozen civilians and the theft of hundreds of sheep. More simply, the attacks and mines instill terror in locals, reducing the number willing to venture into the desert and thus increasing ISIS militants’ ability to move undetected.

Likewise, eastern Hama served as the key front for ISIS expansion in 2020, as the largely empty plains there allowed ISIS cells to easily move between southern Aleppo, Raqqa, and eastern Homs, essentially serving as an important transit node for Badia movement. A regime officer who assisted in community protection operations there in 2021 told this author that the regime believed ISIS’s goal then was to displace remaining unsympathetic locals to better obscure their own movements. Attacks during February and March likely serve a similar purpose, especially if ISIS is hoping to expand its foothold in the area once again.

Civilians Suffer, ISIS Wins

Central Syria is one of the most complex and misunderstood regions of the country today. There is no accurate and comprehensive objective media coverage of daily events. Instead, various local Facebook pages sometimes report on attacks against their community members or that occur in the region, while pro-opposition news accounts spread many rumors of large attacks against regime forces (by ISIS) and civilians (by Iran) in order to drive traffic to their sites and discredit regime and Iranian forces. The lack of accurate information, on the one hand, and a plethora of misinformation on the other, leaves outsiders with at best, only a partial picture of the years-long insurgency and daily life.

The truth is, there is no definitive answer to the question of who is perpetrating the recent attacks against civilians. There is extensive circumstantial evidence that points to ISIS, but criminal gangs and pro-regime forces can never be completely ruled out. Regardless, the shooting and kidnapping of locals, not to mention the near daily tragedy of locals killed by mines, will continue to push civilians out of their villages for the safety of larger towns and deepen distrust between locals and security forces. All of this will strengthen ISIS’s ability to transit the region at will and engage in black market financial operations with the local illicit economy. Security chaos and mistrust has been the key to ISIS’s resiliency in northeast Syria. The corruption and political infighting endemic to Syrian regime forces has left the door wide open for ISIS cells to exploit that same strategy in central Syria.