Wagner May be Out, but Russia remains “In” with Mali

On June 6, 2025, the notorious Russia-backed Wagner Group announced their imminent withdrawal from Mali. Operating in the Sahelian country for three and a half years, the private military company (PMC) has faced its fair share of criticism from the international security community. In October 2022, CEP discussed the potential challenges of the Wagner Group in Mali. Noting the PMC’s preference for excessively violent operations and disregard for international human rights, CEP warned that the PMC would fail to achieve notable gains against the jihadist insurgency and would more likely exacerbate existing factors of instability, such as interethnic conflict, economic insecurity, and ineffective systems of governance. In the three and a half years since Wagner’s deployment, the reality is even worse than we imagined. Transnational and international alliances have been eliminated in favor of a trilateral agreement between the Russian-backed coup leaders of the Sahel, violence against civilians is at a record high, and jihadists remain nothing but determined in their attacks against the state and its forces.

Background

French troops were deployed in early 2013 to counter the growing jihadist threat. Although initially successful in ousting jihadists from their northern strongholds, Operation Serval-cum-Operation-Barkhane, struggled in securing long-term stability. As jihadists continued to expand their influence and evolve into formidable contingents of al-Qaeda and ISIS, Bamako succumbed to successive military coups in August 2020 and May 2021. Growing anti-Western sentiment culminated in widespread protests and the gradual, but forced, withdrawal of French troops and other western-led counterterrorism initiatives in 2022.[1]

Wagner’s performance in the Central African Republic (CAR)—where they successfully repelled rebel forces—persuaded the Malian government to enlist their services. With an agreement formalized in 2021, Wagner troops were officially deployed in December of that year.[2] Under the agreement, Wagner troops would answer to the Malian military (FAMa) and Russian advisors from the Russian Ministry of Defense.[3] Officially, Wagner operations were limited to joint missions with FAMa. However, upon their deployment, Wagner troops sidelined these restrictions, often acting outside of authorized missions and subjecting civilians to new sources of violence and insecurity.

Wagner Score Card

Although deployed in 2021, the Wagner Group did not achieve a notable operational victory until November 2023 when they recaptured the rebel stronghold of Kidal in northern Mali.[4] Despite being a success, the operation targeted Tuareg rebels rather than extremists. Although the state has accused Tuaregs of maintaining ties with militant Islamists,[5] the operation in Kidal confirms Wagner’s inconsistent counterterrorism priorities as well as their inability to effectively repel genuine al-Qaeda and ISIS forces.

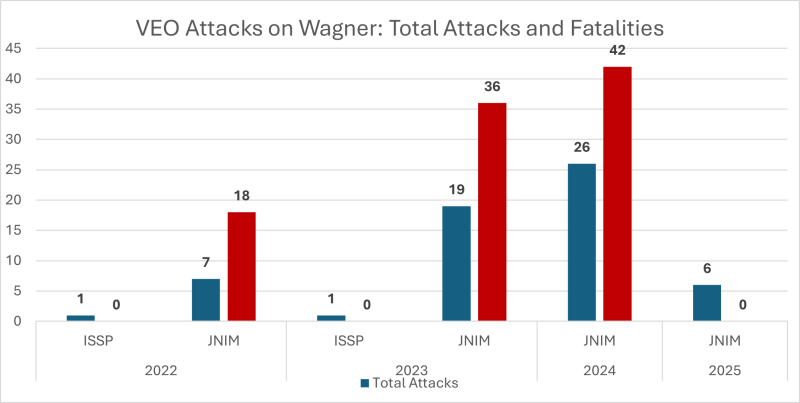

On multiple occasions, al-Qaeda and ISIS fighters carried out lethal attacks resulting in significant Wagner and FAMa casualties. In July 2024, 20 to 80 Wagner forces and an unreported number of Malian troops were killed following two days of fighting involving Tuareg rebels and JNIM fighters in Tinzaouaten, northeastern Mali.[6] Shortly after, in September 2024, JNIM carried out assaults on the national gendarmerie academy, and Modibo Keïta International Airport in Bamako-Sénou, two critical locations in Bamako. JNIM’s brazen attack on the nation’s capital undermined Wagner and the Malian army’s presence as legitimate threats to the advancing extremist group.[7] The airport is not only the Malian army’s main air base, but it is where Russian paramilitaries are based. An estimated 50 to 70 fatalities were reported, despite JNIM claiming hundreds of soldiers were killed or wounded.[8] The attacks continued, further wearing down Wagner’s role as an effective security force. On June 4, 2025—two days before Wagner announced their impending withdrawal—JNIM claimed another bold operation, detonating an explosive at a FAMa-Wagner training camp in the outskirts of Bamako.[9]

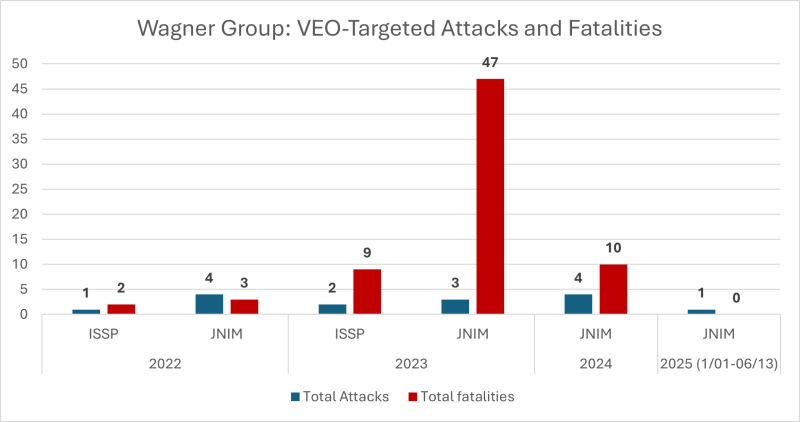

During their tenure from December 2021 until June 2025, Wagner failed to achieve significant advances against VEOs. When comparing Wagner counterterrorism missions and VEO attacks on Wagner forces, the two sides carried out a similar number of operations, suggesting Wagner implemented a tit-for-tat military strategy rather than a maximum pressure campaign against the jihadists. In 2022, Wagner carried out five operations resulting in five fatalities. In 2023, the PMC fared a bit better, carrying out three attacks resulting in 47 JNIM fatalities. However, they were less effective in 2024 when four attacks yielded ten jihadist fatalities. Although Wagner forces were meant to supplement ground-based counterterrorism activities, Wagner never carried out more than four attacks against VEOs, with fatalities never reaching higher than 47. However, Wagner fatalities resulting from JNIM attacks steadily increased every year. Although there were no reported Wagner fatalities in 2025, media sources have yet to confirm JNIM’s claims of a successful attack on a FAMa-Wagner training camp on June 4, 2025.

Given the figures, it is hardly likely that Wagner’s deployment disrupted jihadist networks to any significant degree. Rather, their presence has served as an inconvenience more than a legitimate threat to the jihadist network. Despite their poor track record, the Wagner Group claimed “[m]ission accomplished,” in their Telegram announcement of their impending withdrawal. According to the PMC, they not only eliminated leading jihadist commanders, but also restored the Malian army’s control of all regional capitals.[10]

Wagner Atrocities

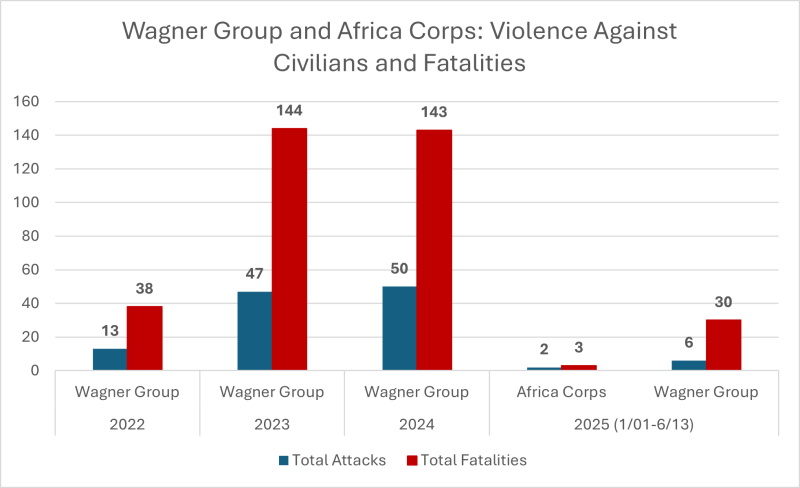

Despite the PMC’s relatively short deployment period, their legacy continues to haunt Mali. The Wagner Group normalized indiscriminate violence, leaving civilians vulnerable to attacks from jihadists, the state, and the state’s proxy counterterrorism forces. Between March 23, 2022, and March 31, 2022, the Malian army and Wagner troops launched a counterterrorism operation in central Mali’s Moura area. An estimated 300 were killed and 51 others were arrested in the “terrorist fiefdom.” However, media sources reported that dozens of people, including civilians, were killed in the attacks, leading U.N. Secretary-General Antonio Guterres to report that Mali’s counterterrorism efforts had “disastrous consequences for the civilian population.”[11]

High-fatality attacks continued throughout their deployment. Between 2022 and 2025, Wagner Group carried out 112 attacks resulting in a total of 355 civilian fatalities. However, attack and fatality figures may be significantly higher considering Wagner carried out counterterrorism operations targeting ethnic Fulani communities accused of cooperating with jihadists despite not having evidence to confirm their suspicions.[12] By targeting Fulani communities under the counterterrorism banner, Fulani civilians would instead be considered militants. On-the-ground sources further confirm that “[s]ecurity forces tend to view populations living in jihadist-influenced areas as collaborators.”[13] Additionally, these figures do not take forced disappearances into account which dilutes the true impact of Wagner’s footprint across Fulani communities. Between January and July 2025, at least 81 Fulani men were reported as forcibly disappeared.[14]

Wagner’s signature heavy-handed approach did not thoroughly integrate proper reconnaissance, resulting in operations and tactics that were rife in corporeal punishment. According to a joint investigation carried out by Forbidden Stories, IStories, Le Monde, and France 24, Wagner reportedly operated six military bases where Malian civilians were detained and tortured. The military bases included Bapho and Nampala in south central Mali, Sévaré and Sofara in central Mali, and Kidal and Niafunké in the northern regions of Kidal and Timbuktu, were reportedly in operation between 2022 and 2024.[15] These camps operated outside of any legal framework as Wagner not only arbitrarily arrested and kidnapped suspects—sometimes denying the victim any contact with the outside world—but also employed fatal and near-fatal forms of torture.[16] The detention centers and their conditions were abhorrent: reports claim prisoners were starved and crowded into former equipment containers.[17]

Africa Corps

Wagner is expected to fully withdraw from the region by the end of July 2025,[18] with additional media reports suggesting Wagner intends to quietly switch out the entirety of their Africa-based forces with the Africa Corps.[19] Unlike the Wagner Group, the Africa Corps are classified as a direct subsidiary of the Russian Ministry of Defense. There are approximately 1,500 Africa Corps troops stationed in Mali who will be primarily concentrated in Bamako. While Wagner focused on ground combat, the Africa Corps is more discerning in their operations and will reportedly focus on training, logistics, and targeted operations, including targeted airstrikes.[20]

The Africa Corps will also benefit from training and logistical support from Russian military advisers, suggesting the potential for better compliance to military protocol and international humanitarian law.[21] Although the Africa Corps answers to the Russian military, it is worth noting that 70 to 80% of the Africa Corps is reportedly made up of former Wagner members.[22] If the Wagner contingent is not required to undergo corrective training, it is possible they will carry their trigger-happy activities into the Africa Corps operational fold.

It is unlikely that Mali’s security environment will undergo significant changes as Wagner departs. However, Wagner’s departure could represent a turning point in the level of violence against civilians. Wagner’s complete withdrawal also offers a solution, albeit indirectly, to demands from the international community regarding deployed foreign forces who carry out crimes against humanity. Despite minimal efforts to investigate Wagner’s crimes against civilians,[23] Mali’s coup government never established accountability mechanisms to respond to violence carried out by Wagner and other state forces. Without Wagner, the coup government could further delay investigations into the PMC’s illicit activity and further deny justice to the countless civilians subjected to Wagner’s ruthless violence.

Conclusion

Three years ago, CEP expressed great concern for Russian intervention in Mali, noting the incompatibility of defense-heavy counterterrorism responses and increasingly vulnerable populations:

If the countries of the Sahel seek sustainable regional security, the Kremlin cannot be a key player in determining the region’s counterterrorism response. Defeating insurgent networks will require far greater regional collaboration and coordination that goes beyond kinetic operations. Stabilization efforts will require political, developmental, and humanitarian instruments to offset the destruction caused by the constantly evolving extremist threat.

The past three years in the Sahel have seen record breaking levels of violence, made only worse by the Wagner Group and its security counterparts. Unfortunately, our sentiments have not changed. One key difference is that what was once just the “constantly evolving extremist threat,” can now be reclassified as the “constantly evolving extremist and state-sanctioned threats.” Significant changes are needed to break ongoing cycles of insecurity to deliver a stable future for millions across the Sahel. Agents of change must also be subject to change; however, repackaging elements of merciless violent counterterrorism forces will serve no purpose other than to metastasize the conflict.

[1] “Britain to withdraw troops from Mali peacekeeping force,” Reuters, November 14, 2022, https://www.reuters.com/world/uk/britain-withdraw-troops-mali-peacekeeping-force-2022-11-14/; Jason Burke, “International troops quit Mali as violence and Moscow’s influence grow,” Guardian, November 17, 2022, https://www.theguardian.com/world/2022/nov/17/troops-quit-mali-violence-moscow-influence.

[2] “Mali and Russia sign deal on nuclear energy during Goïta's Moscow visit,” Rédaction Africanews, June 24, 2025, https://www.msn.com/en-gb/news/world/mali-and-russia-sign-deal-on-nuclear-energy-during-go%C3%AFta-s-moscow-visit/ar-AA1HgV5y.

[3] John Lechner and Sergey Eledinov, “Wagner mercenaries declare 'mission accomplished' in Mali,” Responsible Statecraft, June 16, 2025, https://responsiblestatecraft.org/wagner-group-africa-2672360360/.

[4] “Mali's army says it's captured rebel stronghold of Kidal,” Reuters, November 13, 2023, https://www.reuters.com/world/africa/malis-army-claims-capture-rebel-stronghold-kidal-2023-11-14/.

[5] “Mali is still unsafe under the military: why it hasn’t made progress against rebels and terrorists,” The Conversation, August 8, 2024, https://theconversation.com/mali-is-still-unsafe-under-the-military-why-it-hasnt-made-progress-against-rebels-and-terrorists-236252.

[6] Chris Ewokor and Lucy Fleming, “Mali army admits 'significant' losses in Wagner battle,” BBC News, July 30, 2024, https://www.bbc.co.uk/news/articles/cq5xvl1111yo.

[7] Jean-Hervé Jezequel, “The 17 September Jihadist Attack in Bamako: Has Mali’s Security Strategy Failed?,” International Crisis Group, September 24, 2024, https://www.crisisgroup.org/africa/sahel/mali/attaque-jihadiste-du-17-septembre-bamako-lechec-du-tout-securitaire-au-mali.

[8] Jean-Hervé Jezequel, “The 17 September Jihadist Attack in Bamako: Has Mali’s Security Strategy Failed?,” International Crisis Group, September 24, 2024, https://www.crisisgroup.org/africa/sahel/mali/attaque-jihadiste-du-17-septembre-bamako-lechec-du-tout-securitaire-au-mali.

[9] Franklin Nossiter, “Mali and Russia Restructure Their Security Partnership – But to What End?,” International Crisis Group, June 10, 2025, https://www.crisisgroup.org/africa/sahel/mali-russia-internal/mali-and-russia-restructure-their-security-partnership-what-end.

[10] Mark Banchereau, “Wagner Group leaving Mali after heavy losses but Russia’s Africa Corps to remain,” Associated Press, June 6, 2025, https://apnews.com/article/mali-wagner-russia-withdraws-b29349be737cbc14dfc435b3536711eb.

[11] “U.S. calls reports of many killed in Mali 'extremely disturbing',” Reuters, April 4, 2022, https://www.reuters.com/world/africa/us-calls-reports-many-killed-mali-extremely-disturbing-2022-04-03/; Carly Petesch, “300 killed by Mali’s army and foreigners, says rights group,” Associated Press, April 5, 2022, https://apnews.com/article/russia-ukraine-human-rights-watch-mali-africa-europe-2543fed110a0930e42a1972c4c39e885; “Mali Says 203 Killed in Military Operation in Sahel State,” Agence France Presse, April 1, 2022, https://www.voanews.com/a/mali-says-203-killed-in-military-operation-in-sahel-state/6512181.html.

[12] Agence France Presse, “Wagner 'Atrocities' Give Mali Jihadists Ammunition for Propaganda,” Voice of America, November 12, 2022, https://www.voanews.com/a/wagner-atrocities-give-mali-jihadists-ammunition-for-propaganda-/6832144.html.

[13] “International investigation reveals Wagner Group's secret prisons in Mali,” RFI, June 12, 2025, https://www.rfi.fr/en/africa/20250612-international-investigation-reveals-wagner-group-secret-prisons-in-mali-russia.

[14] “Mali: Army, Wagner Group Disappear, Execute Fulani Civilians,” Human Rights Watch, July 22, 2025, https://www.hrw.org/news/2025/07/22/mali-army-wagner-group-disappear-execute-fulani-civilians.

[15] “International investigation reveals Wagner Group's secret prisons in Mali,” RFI, June 12, 2025, https://www.rfi.fr/en/africa/20250612-international-investigation-reveals-wagner-group-secret-prisons-in-mali-russia.

[16] Guillaume Vénétitay, “Torture and Forced Disappearances: Inside Wagner’s Secret Prisons in Mali,” Forbidden Stories, June 12, 2025, https://forbiddenstories.org/torture-wagners-prisons-mali/.

[17] “International investigation reveals Wagner Group's secret prisons in Mali,” RFI, June 12, 2025, https://www.rfi.fr/en/africa/20250612-international-investigation-reveals-wagner-group-secret-prisons-in-mali-russia.

[18] Liam Karr and Kathryn Tyson, “Wagner Out, Africa Corps In: Africa File, June 12, 2025,” Institute for the Study of War, June 12, 2025, https://www.understandingwar.org/backgrounder/wagner-out-africa-corps-africa-file-june-12-2025.

[19] Ryan Bauer, “The Wagner Group Is Leaving Mali. But Russian Mercenaries Aren't Going Anywhere,” RAND, June 12, 2025, https://www.rand.org/pubs/commentary/2025/06/the-wagner-group-is-leaving-mali-but-russian-mercenaries.html.

[20] Alex Blackburn, “Wagner’s Exit from Mali Marks Shift in Russian Strategy Amid Rising Instability in the Sahel,” Bloomsbury Intelligence Security Institute, June 20, 2025, https://bisi.org.uk/reports/wagners-exit-from-mali-marks-shift-in-russian-strategy-amid-rising-instability-in-the-sahel.

[21] Alex Blackburn, “Wagner’s Exit from Mali Marks Shift in Russian Strategy Amid Rising Instability in the Sahel,” Bloomsbury Intelligence Security Institute, June 20, 2025, https://bisi.org.uk/reports/wagners-exit-from-mali-marks-shift-in-russian-strategy-amid-rising-instability-in-the-sahel.

[22] Liam Karr and Kathryn Tyson, “Wagner Out, Africa Corps In: Africa File, June 12, 2025,” Institute for the Study of War, June 12, 2025, https://www.understandingwar.org/backgrounder/wagner-out-africa-corps-africa-file-june-12-2025.

[23] Paul Nije, “Mali to investigate claims soldiers 'executed' women and children,” BBC News, February 22, 2025, https://www.bbc.co.uk/news/articles/c04zlv32rdqo.

Stay up to date on our latest news.

Get the latest news on extremism and counter-extremism delivered to your inbox.