Introduction

In the past decade, the Sahel has seen a surge of insurgent activity, subjecting millions of civilians to daily violence, displacement, and insecurity. Beginning in Mali in 2012 and Burkina Faso in 2015, violent extremist organizations (VEOs) have entrenched their networks across the surrounding region, causing destruction at a greater speed and larger scale in each new theater of operation. Other domestic factors, such as political unrest, economic instability, and interethnic struggle have further compromised tenable and long-term solutions to the region now considered the “global epicenter of terrorism deaths.”* The crisis has created a culture of violence that has affected every level of society, with civilians facing the worst of the brutality.

Burkina Faso has contended with the same destabilizing actors as Mali, subsequently launching internationally backed and local campaigns against the homegrown Ansarul Islam, the al-Qaeda affiliate Jama’at Nusrat al-Islam wal Muslimeen (JNIM), Islamic State West Africa Province (ISWAP) - Greater Sahara Faction, Islamic State Greater Sahara (ISGS) and its current rebranded moniker Islamic State Sahel (IS Sahel), in the process. Military support from international partners failed to contain the conflict and two successive military coups in 2022* led to the complete breakdown of Western-Burkinabe relations. After establishing a defensive and cooperative regional bloc called the Alliance of Sahel States or l’Alliance des États du Sahel (AES) in September 2023,* Burkina Faso and its fellow military-run neighbors Mali and Niger, have prioritized isolationist policies and questionable deployments in their response to violent extremists in the region.

According to the Institute for Economics and Peace (IEP), terrorism in Burkina Faso has worsened every year since 2014, and as of 2024, the country ranks first in the Global Terrorism Index’s (GTI) assessment of countries most impacted by terrorism.* In less than a decade, the conflict has resulted in the deaths of thousands and the displacement of two million others. In December 2024, the United Nations reported that almost half of Burkinabe territory has fallen to the control of terrorist groups, whereas media reports in January 2025 have asserted that figure is closer to 80 percent.* Projections remain bleak, as the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR) estimates that 3.65 million Burkinabes—99 percent of the total population—will be internally displaced by the conflict in 2025.*

Civilian-Led Militias

To counter the rapid spillover of jihadist violence from Mali into Burkina Faso, civilian-led militias began emerging in 2014 to counter jihadist activity. Among the first were the Koglweogo and Dogon self-defense militias in the eastern and western regions of Burkina Faso. However, these groups have proven highly controversial as they regularly target marginalized ethnic groups—particularly the nomadic Fulani—who they claim are sympathetic towards violent Islamists.*

Despite the controversy surrounding the ethnic militias, in early 2020, the Burkinabe government formally sponsored the deployment of community defense troops known as the Volunteers for the Defense of the Homeland (VDPs) to reinforce Burkina Faso’s national counterterrorism structure.* The VDP provided a significant infusion of manpower to the Burkinabe defense system as 90,000 VDP troops were reported by November 2022, significantly outnumbering the Burkina Faso Armed Forces (FABF).* Estimates of FABF troop numbers vary widely, with some sources reporting 11,200 active-duty members,* and other sources claiming there are somewhere between 15,000-20,000 FABF troops.* Additional recruitment cycles occurred in March 2025, with Burkina Faso’s military seeking 14,000 more soldiers to offset the continued threat of al-Qaeda and ISIS.* With close to 100,000 volunteer troops, questions surround how the military regime can thoroughly enforce models of efficiency and compliance to rule of law.

The VDP is further categorized by its national and local units. The national VDP are “practically soldiers” and are expected to eventually join the army. National VDP receive the same equipment and are deployed alongside state troops in joint operations. The local VDP are trained by the police or gendarmerie closest to their own communities. Of the two sections, the national VDP is significantly smaller than its local counterpart as revealed by an October 2022 recruitment drive which sought to enlist 15,000 national VDP in comparison to 35,000 local VDP.* The VDP fail to respect delineated responsibilities, as militiamen across both units have been accused of blurring the lines of their mandated roles and introducing additional sources of conflict to a severely dire humanitarian crisis.

Civilian-led militias have exacerbated the social and political conditions already degraded by violent extremists.

Civilian-led militias have exacerbated the social and political conditions already degraded by violent extremists. Their inclusion within the state’s counterterrorism infrastructure has transformed the environment into a multivariable conflict that is solely met with heavy handed counterterrorism responses. Accordingly, Burkinabe counterterrorism objectives continue to be obscured and overshadowed by the transgressions of its nascent defense units as reports of extrajudicial violence and corruption are rampant among the militias ranks. These units occupy a dangerous position as they have coopted counterterrorism operations to militarize and justify biased historical rivalries. Their formalization has not only increased unprecedented levels of violence across all sides of the conflict, but they have also contributed to the long-term delegitimization of the state and its security forces.

Consequently, the volume of VDP forces, partnered with insufficient training and questionable motives, portends significant humanitarian risks. Rather than being protected from insurgents, civilians now contend with the daily fear of violence from both insurgents and state-sponsored forces. This report will further explore how civilian-led defense units have introduced a pervasive culture of violence that has debilitated overall civilian safety, degraded interethnic relations, and delegitimized the state to the point of encouraging civilian support of violent extremists.

Conflict of Interest Breeds Culture of Violence

Since the deployment of civilian-led militias, and specifically after the introduction of the VDP, a fatal trend has emerged where civilians are subject to significant violence from both VEOs and state auxiliary groups. Not only has the number of violent incidents against civilians increased, but civilian fatalities have exponentially escalated, suggesting that disproportionate levels of violence are regularly employed across the conflict.*

[This report defines] “culture of violence” as the way in which violent behaviors are prioritized, normalized, and perpetuated across a conflict.

Although the Geneva Conventions—the international legal framework intended to prevent the worst atrocities of war—forbid attacking civilians and causing unnecessary suffering, loss, and harm, the increase of civilian fatalities across all sides of the conflict demonstrates new, and severely dangerous, interpretations of the limitations of warfare. Throughout this report, I define “culture of violence” as the way in which violent behaviors are prioritized, normalized, and perpetuated across a conflict. Accordingly, behavioral norms established by progovernment militias (PGMs)—those aligned with the state or under the purview of state defense structures—have a strong influence on their personnel. As PGM leaders carry out operations that include disproportionate levels of violence, personnel are more likely to adopt and deploy similar levels of violence in their own patrol missions. When PGMs adopt and impulsively carry out violent tactics, it is more likely that their personnel will carry out violence without proper discernment, and will carelessly open fire or target actors in the environment not directly affiliated with their cadre.* Given this logic, as PGMs adopt more aggressive operations, namely indiscriminate attacks, there is a greater probability that this method will become institutionalized and lead to significant increases in fatalities by all personnel operating within the state’s defense network.

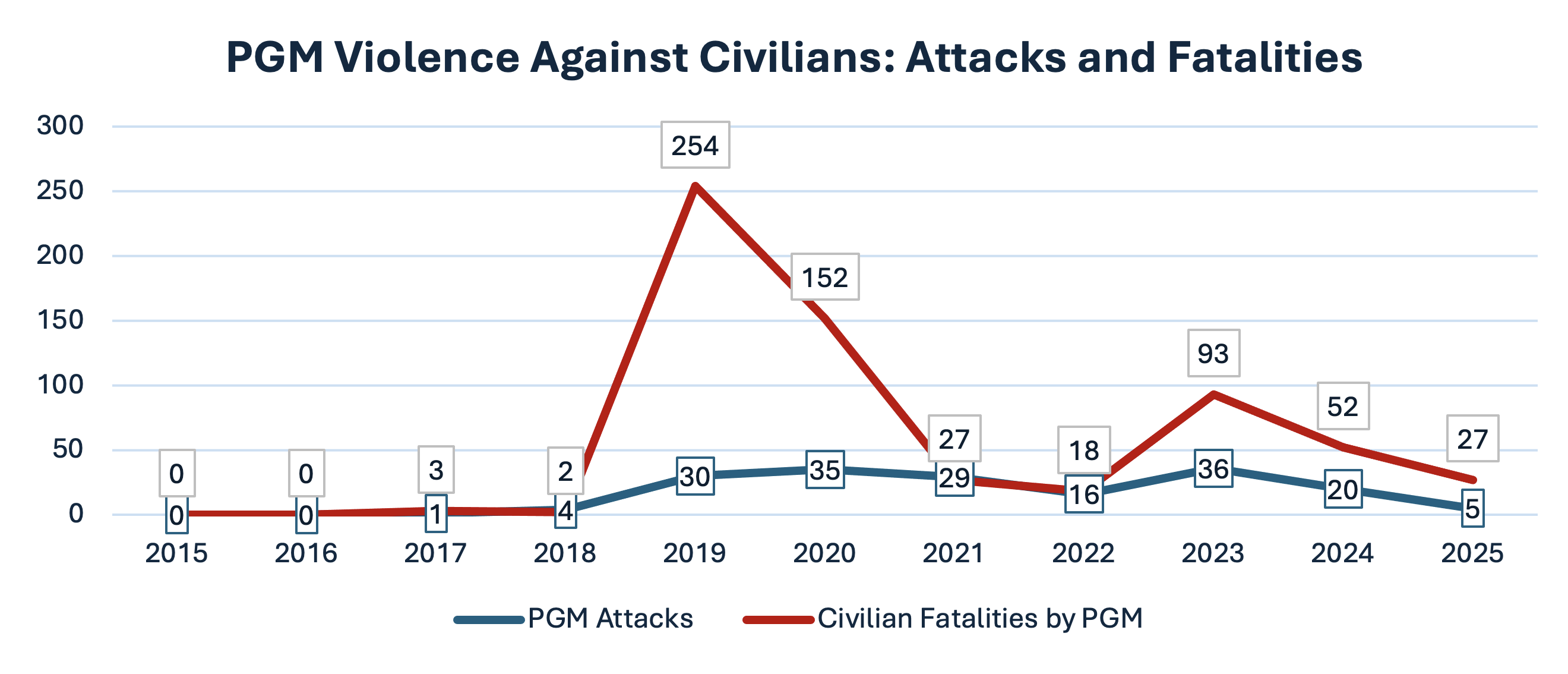

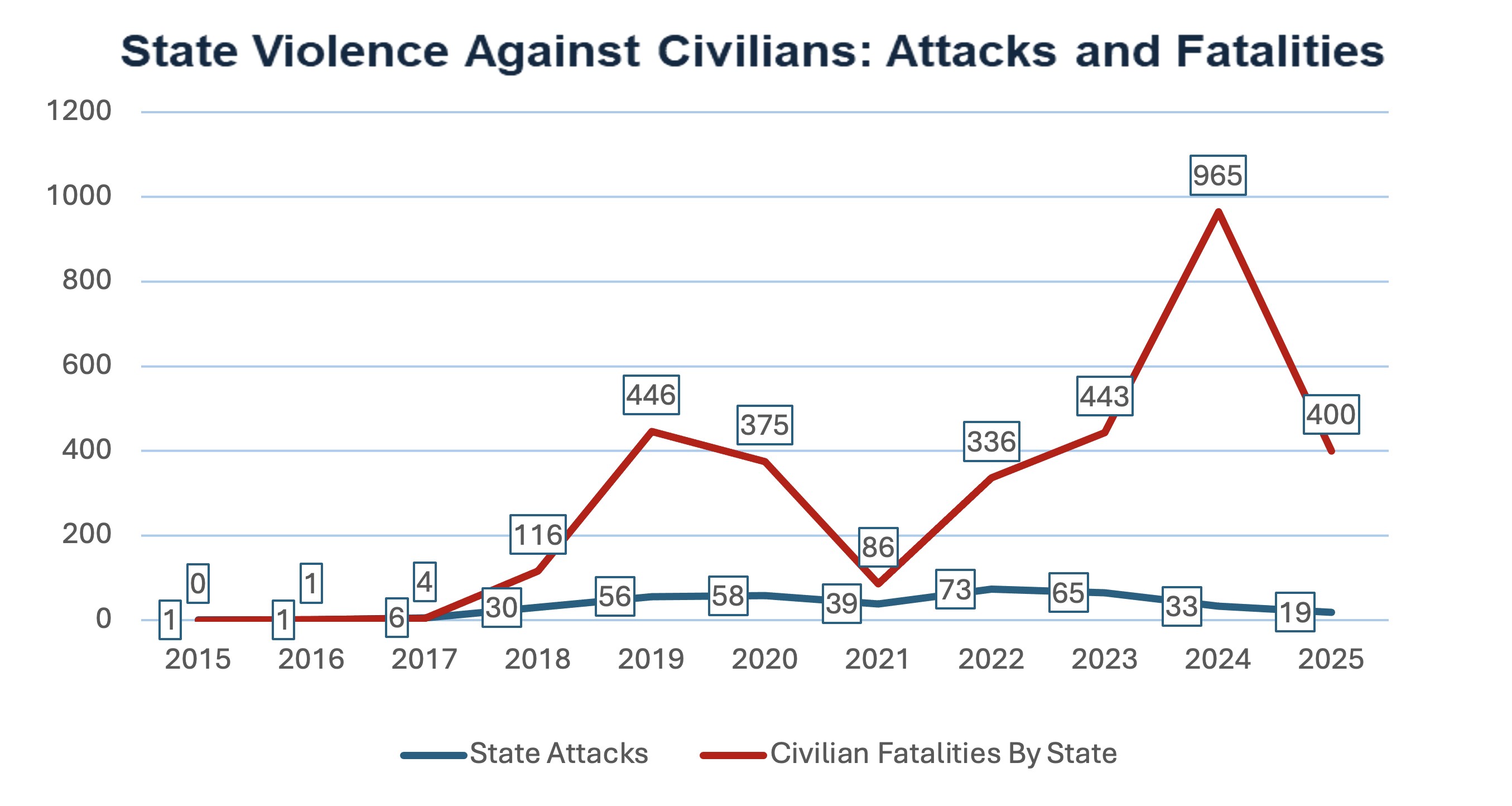

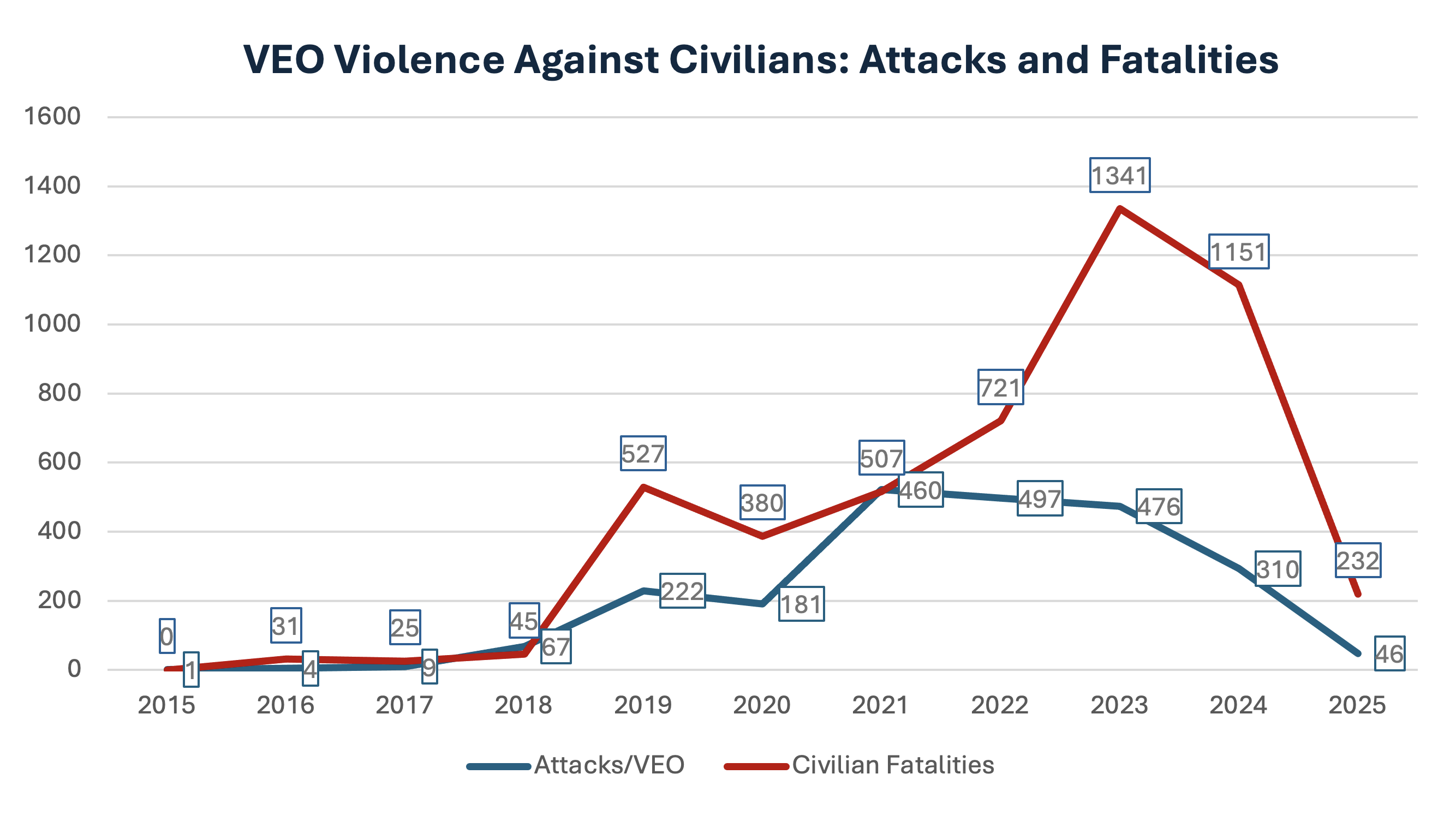

In quantifiable terms, the culture of violence can be understood by the annual number of attacks and civilian fatalities within the conflict. These figures provide numerical insight and a visual synopsis into the normalization of fatal violence as a strategy of both insurgency and counterinsurgency. Below, the two charts examine the increase in state and PGM violence against civilians and the increase in VEO violence against civilians. Analyzing the number of attacks carried out by conflict actors and the associated number of fatalities may seem myopic in the context of protracted insurgencies but comparing how drastically variables change from one year to the next based on the deployment of civilian-led militias exposes how severely these agents change the dynamics of the crisis and how quickly they can become agents of predation and additional sources of conflict.

Note: when exporting data from ACLED’s dataset, I searched for “violence against civilians.” The events were limited to the timeframe of January 1, 2015, until June 4, 2025. PGM forces include VDP and Koglweogo.

PGM attacks significantly increased in 2019 when the Koglweogo militia first formalized its efforts.101 Attacks jumped from four in 2018 to 30 in 2019, and fatalities significantly increased from two to 254 in the same timeframe. Interestingly, following the absorption of the Koglweogo into the VDP in 2020, fatalities from PGM violence decreased from 152 in 2020 to 27 in 2021 with fatalities remaining under 100 through June 4, 2025. It is possible that inconsistent reporting of attacks in crisis areas and the oft-cited difficulty of differentiating between Koglweogo and VDP forces from military forces could have affected the accuracy of these numbers. Accordingly, in April 2023, suspected military and VDP forces carried out brutal attacks on two villages in northern Burkina Faso. On April 20, 2023, more than 150 civilians were killed in a northern village by men allegedly from Burkina Faso’s defense and security forces as well as the VDP.* Another attack on April 23, 2023 saw men “dressed in military uniforms” kill 60 people in the northern village of Karma.* Similarly on November 5, 2023, men described as wearing military uniforms descended on the village of Zaongo, central Burkina Faso, killing dozens of civilians. The government dismissed accusations of extrajudicial violence and instead asserted that jihadists disguised themselves as soldiers.* In 2025, VDP forces multiplied the lethality of their attacks, averaging a little more than five fatalities per attack compared to 2024 which averaged less than three fatalities per attack. Notably, in a two-day attack in March 2025, pro-government militias were implicated in another mass civilian killing in Solenzo, western Burkina Faso that shared similar details to the Karma and Zaongo attacks mentioned earlier. Men in VDP uniforms as well as green t-shirts brandishing the insignias of other local militias killed at least 58 Fulani in the two-day massacre.* In each instance, perpetrators wore military uniforms, but it was uncertain if they were from the national army, the VDP, or both, further preventing evidence of who was responsible and who to hold accountable for the atrocities.

Note: when exporting data from ACLED’s dataset, I searched for “violence against civilians.” The events were limited to the timeframe of January 1, 2015, until June 4, 2025. State forces include the military and police forces of Burkina Faso.

Violence committed by the military and police forces was initially less fatal following the integration of the Koglweogo, with 71 less fatalities reported in 2020 despite two more attacks than in 2019. 2021 may have seen 20 less attacks than in 2020, but fatalities drastically declined from 2020 with a total of 86 fatalities or less than a quarter of the 375 fatalities reported in the previous year. The decline could be due to an increase in reliance on the Koglweogo in local operations which would offset the potential for state violence. However, state violence and civilian fatalities exponentially increased between 2022 and 2024 when the country underwent two consecutive coups by military leaders who further demanded the withdrawal of western troops. The security vacuum resulting from political instability and the significant shift from a multilateral counterterrorism strategy in favor of domestic forces further debilitates the quality of operation protocol and commitment to international human rights standards. Between January 1 and December 30, 2024, the number of fatalities were almost double that of 2023, with a total of 965 civilians killed in state-sponsored attacks. The significant increase in state violence was most likely due to the increasing fatality of VEO attacks against civilians in the same timeframe. Fatality figures continued to disproportionately increase in comparison to attacks in 2025. Between January 1, 2025, and June 4, 2025, attacks have been especially brutal, as these first five months already recorded 400 fatalities. It is possible the military may target civilians solely for their proximity to jihadist hot spots,* however, these deadly and at times unjustified reprisal attacks are less strategic and more detrimental to political stability, leading to additional problems in the long run. Despite carrying out operations to uproot jihadist groups, the military instead exposes civilians to both the dangers of terrorism and the disastrous effects of mishandled counterterrorism operations.

Figures confined to the timeframe of January 1, 2015 and June 4, 2025. VEO actors include JNIM: Group for Support of Islam and Muslims, Islamic State West Africa Province (ISWAP) - Greater Sahara Faction, Islamic State Sahel Province (ISSP), Islamic State Sahel Province (ISSP), Ansarul Islam, Islamic State in the Greater Sahara (ISGS), Al Mourabitoune Battalion, and Islamist Militia (Burkina Faso). All data gathered from Armed Conflict and Location Event Database.

The number of VEO attacks against civilians is also notable, as it likely signals the inability of state forces to protect their denizens despite deploying additional support. Following the launch of the VDP, VEO attacks against civilians slightly decreased, with 181 attacks compared to 222 in 2019. The number of fatalities also notably decreased, falling from 527 in 2019 to 380 in 2020. The number of civilian fatalities from VEO violence also decreased in 2020 and 2021, potentially due to civilians joining the just-launched VDP to protect their communities and offset the violence. Accordingly, the reason for the decrease could be due to VEO unfamiliarity with VDP tactics and organization, allowing for greater success of VDP operations and subsequently, their ability to protect civilians. However, following VDP recruitment drives in late October 2022 and early 2023, it was expected that VEOs would increase the number of attacks against civilians or carry out more lethal attacks in order to prevent civilian alliance with the state. Though the overall number of attacks decreased, a disproportional increase in fatalities from 2021 onwards confirms this theory. Although 2022 and 2023 saw similar levels of attacks, with 497 in 2022 and 476 in 2023, fatalities dramatically increased from 721 in 2022 to 1341 in 2023. Despite a significant decrease in attacks in 2024—310 compared to 476 in 2023—the number of fatalities mirrored that of 2023, with 1151 fatalities reported. These results indicated the increasing lethality of VEO attacks but may also indicate how inadequately prepared VDP troops are, placing civilians at greater risk of being targeted or massacred in VEO attacks. Between January 1, 2025, and June 4, 2025, VEO activity has proved slightly more fatal than in 2024, with around five fatalities per attack in comparison to 2024, when attacks resulted in less than four fatalities per event. Considering the speed and increasing intensity with which VEOS are carrying out fatal attacks, the Burkinabe coup government is far from making credible improvements in stability and security, ultimately wearing down civilian loyalty to the state and its larger security network.

Variables Perpetuating the Culture of Violence

PGMs have severely compromised civilian safety, as state auxiliary forces do not refrain from gruesome tactics similar to those employed by VEOs. According to one interview with a resident of a local village, violence “doesn’t mean anything anymore to people” given the scale and regularity of bloodshed.* As PGM forces are a sanctioned layer of security throughout the regime’s counterterrorism matrix, their activities symbolize and standardize how the state and its actors carry out counterterrorism engagement and crisis response. The cyclical nature of the culture of violence further suggests attacks are expected to increase or become deadlier following particularly egregious acts of violence, as they would set a new standard for acceptable levels of violence carried out in the name of counterterrorism.

The culture of violence is perpetuated across the conflict as state oversights have enabled civilian-led militias to conduct counterterrorism operations without proper training in combat and human rights laws. Without clear expectations, civilian-led militias follow their own defense paradigms, often allowing reductive rationale to drive their actions. State negligence—particularly the reasons stated above as well as the lack of accountability frameworks in response to militarized ethnic bias and the elimination of dialogues between local leaders and violent extremists—have amplified social conditions that not only facilitate the culture of violence but also introduce new sources of long-term conflict.

Armed Inadequacy: Training and Operational Deficits of the VDP

The VDP are reportedly provided with two weeks of training in weapons—or “basic firearm skills” as reported by local sources*—human rights, and discipline.* This rudimentary onboarding process has had detrimental effects as human rights violations have metastasized under the VDP. As VDP troop numbers inflate, it is unlikely that onboarding processes will be retrofitted to meet the demands of an overflowing defense network. Spread throughout Burkina Faso’s 351 communes, it is dubious whether new recruits are provided adequate supervision and human rights training to eliminate potential abuse and corruption.* Despite their state-sponsorship, the VDP is not given carte blanche and cannot perform duties outside the scope of their responsibilities in preserving law and order in the area, a precondition that is flippantly observed.*

The VDP was deployed at the height of the insurgency to fill security gaps left by an increasingly defeated national army. However, VDP troops served as pawns for the national forces and even the state. Between October 2020 and March 2021—soon after VDP formalization—the “Djibo agreement” between the state and JNIM mandated a cessation of violence between the jihadist network and the armed forces. The VDP were not included in the pact and JNIM instead directed their attacks towards the fledgling defense unit.* Although the VDP is categorically a self-defense unit, the army reportedly refrained from engaging in battle and instead relegated the VDP to the frontlines without much guidance.* The VDP served as the first line of defense, resulting in many troops abandoning their stations, and more importantly their assigned communities, between 2021 and 2022.*

The treatment of the VDP as expendable units with conflicting levels of responsibility has fostered a disorganized and easily manipulated security environment. The VDP are assigned to specific jurisdictions, but on-the-ground interviews reveal that these parameters are not strictly enforced or monitored, easily allowing militias to push the perimeter of their activities. According to the International Crisis Group, some civilian militias covered entire provinces.* Civilian militias exist on the periphery of the defense system, yet they sometimes cast themselves as official troops within the national army, further confusing civilians who already have issues in discerning VDP troops from national security forces and even untrained civilians posing as militia members.* Given the predatory nature of some of the VDP, the expansion of their site of control also increases the number of people at the mercy of heavy handed protocol against perceived jihadist sympathizers. Without strict guidelines and accountability mechanisms, every civilian is vulnerable to the whims of the VDP.

Local interviews with residents reveal that troops sometimes abandon their weapons and flee villages targeted by VEOs, leaving civilians to fend for themselves.* Notably, on August 24, 2024, JNIM militants ambushed the town of Barsologho, in north central Burkina Faso. According to media reports, up to 600 civilians were shot dead and 140 civilians were left injured.* The majority of those killed were civilians forced by troops from state-sponsored militias to dig a vast defensive trench network on the town’s periphery.* Notably, the militias did not provide civilians with any defensive tools, essentially signing off on civilians digging their own graves if faced with a jihadist ambush. According to French reports on the Barsologho massacre, the Minister of Civil Service prompted villages to construct trenches as part of an initiative to “organize [themselves] and have [their] own response plan to an attack.”* The Barsologho massacre not only reveals the defensive ineptitude of the VDP, but also demonstrates that civilian safety is a suggestion and not a standard within Burkinabe counterinsurgency protocol.

In many cases, poorly trained and inadequately armed VDP members are soft targets for terrorist groups. Hundreds have died in ambushes or been killed by roadside improved explosive devices (IEDs) since the VDPs were first created at the end of 2019.* VEOs intentionally targeted these militias from the very beginning to not only debilitate the state’s overall counterterrorism abilities but also weaken civilian confidence in the state’s effective delivery of security. In one instance following the announcement of recruitment programs in Burkina Faso, violent extremists increased their activity. Following the October 2022 announcement for an additional 50,000 VDP recruits, the International Crisis Group noted figures compiled by the Armed Conflict Location and Event Database between January 1, 2023 and October 6, 2023 demonstrating an increase in jihadist attacks against VDPs. In that 10-month period, 644 VDPs were killed in 148 attacks.* Although militant Islamists did not always claim responsibility for the attacks, HRW claimed villagers were able to identify the perpetrators as belonging to the insurgency based on methods of attack, choice of targets, and their clothing. Targeted villages were locations where recruitment for the VDP took place, leading to the insurgents launching retaliatory attacks against these communities reportedly loyal to the state.*

Civilian defense forces that lack proper training will potentially resort to questionable tactics in eliminating threats, and a government “will tolerate these informal armed groups as long as the violence they commit is consistent with strategic goals and as long as the government is not held accountable for them.”* Arbitrary assessments of who is a terrorist or who sympathizes with jihadists have informed particularly brutal acts of violence against civilians. On April 20, 2023, the Burkinabe army carried out a mass killing in Karma, northern Burkina Faso, in retaliation for a nearby terror attack that targeted the army and VDP. The forces reportedly rounded up inhabitants and subsequently shot and killed 147 people in retaliation for “purposely” not warning the troops of terrorist movements.* On February 25, 2024, the Burkinabe defense forces carried out one of their most fatal and arbitrarily informed mass killings against supposed jihadist sympathizers. In a twin ambush targeting the northern villages of Nondin and Soro, the military killed 223 civilians, including 56 children.* The large number of child fatalities underscores the negligence of the defense forces in properly identifying legitimate terror threats.

Civilian-led militias do not just carry out high-casualty acts of violence, they have also been accused of gruesome murders that they later detailed in videos across social media. Two separate videos distributed in July 2024 show self-described militiamen severely mutilating corpses and in some cases committing cannibalism.* Although the military has not verified if the assailants were military personnel, one of the perpetrators was wearing a military uniform.* By November 2024, Burkina Faso’s armed forces alleged they would launch investigations looking into the atrocities, but further developments into the case have not been reported as of 2025.* Interviews with Burkinabe citizens further reinforce that the PGMs trigger-happy tactics have resulted in “great distrust” towards the government.*

As VEOs consistently increase their confrontations with PGMs, civilians keep score of the relative strength and motivations of the two sides. When PGMs abandon communities, civilians are left with no choice but to submit to the authority of jihadists and eschew support of the state’s forces, further legitimizing VEOs as the more forceful and competent actor in the ongoing insurgency.

Militarized Ethnic Bias

As militia training becomes more ceremonial than a strict guideline of expectations, VDP forces have redefined their counterterrorism responsibilities in line with an increasing culture of violence. The VDP have foregone intelligence, surveillance, and reconnaissance—the essential components of deliberate and risk-mitigating military operations—in favor of vengeful narratives and socially perpetuated fallacies as their counterterrorism raison d’etre.

Reasons for an increase in violence against civilians could be reduced to being in the wrong place at the wrong time. However, previous histories of ethnic-based targeting further expose the dangerous reality of Burkina’s quasi-legal security forces. Narratives conflating ethnic minorities with violent extremists likely influence inadequately trained VDP troops to arbitrarily target specific communities, primarily the Fulani.* The pastoral Fulani and the Dogon, an ethnic group of sedentary farmers, have a tense history of power struggles and land access disputes. These hostilities have only become militarized in recent years, with the Dogon-heavy civilian-led militias often being accused of targeting the Fulani under the pretext of counterterrorism.* Aggressive violence has become an inescapable reality for the marginalized group, as a January 2025 interview with a local Fulani noted his uncle was arrested and beaten by soldiers claiming they were “conducting a security operation.”* Despite reports of egregious violence, Burkina Faso’s military government announced plans to recruit an additional 14,000 VDP forces.* The announcement came days after the VDP carried out a two-day massacre in the western province of Banwa. Between March 10 and 11, the VDP killed dozens of civilians, many of whom were ethnic Fulani.*

The VDP’s predilection for prejudiced attacks is widely acknowledged, even resulting in human rights groups, such as the Collective Against Impunity and Stigmatization of Communities (CISC), in formally denouncing the group for bypassing the rule of law and directing violence at specific ethnic and racial groups.* From the outset, civilian militias have been far from representative of the entire population, with the VDP recruitment process often favoring the sedentary Mossi, Foulse, Gourmantche, and Songhai communities and further castigating the Fulani* who are not normally recruited.* These biases against ethnic minorities exist absent the counterterrorism context and have become an oft-cited justification for some of the most gruesome operations. Anti-Fulani sentiment is also perpetuated within the VDP, as one Fulani woman named Rainatou noted that once her neighbors joined the VDP, they stopped interacting with Fulani families. Rainatou last interacted with her neighbors when they arbitrarily targeted and killed her husband.* By scapegoating the Fulani, the VDP have turned prejudice against a minority group into targeted, and often fatal, violence.

Although comprising 14 percent of the overall population in Burkina Faso, the Fulani community has faced the brunt of civilian-targeted violence committed by the state and PGMs during the insurgency, as they make up more than half of the casualties in these attacks.* Between 2015 and 2023, more than 3,000 Fulani were killed across Mali and Burkina Faso.* Not so coincidentally, this time period coincides with the deployment of PGMs across both countries.* Fulani-targeted violence continued to escalate at increasingly worrying levels, and in the last three months of 2023 CISC reported 250 extrajudicial killings of Fulani members—triple the number reported in the previous four months of the same year.*

Civilian-led militias engage in high levels of violence against civilians with impunity, as made evident by the regularly documented crimes committed by the VDP and its precursors. Included among those crimes are the unjustified abduction of individuals, extrajudicial killings of the Fulani, and superfluous use of violence in response to petty crimes such as breaking curfew.* One of the earlier Fulani-targeted reprisal attacks occurred in Yirgou in December 2018. After jihadists targeted and killed six within a community with Koglweogo-links, the Koglweogo ambushed Fulani communities in Yirgou, resulting in 47 deaths.* A similar attack that took place over the span of three days in January 2019, saw VDP predecessor Koglweogo kill up to 220 Fulani civilians. Further compromising the state’s commitment to justice, the Burkinabe government never condemned the attacks. Instead, the Koglweogo were lauded and formalized into the VDP while also being provided government arms to aid the counterinsurgency.* In February and May of 2023, the Fulani community was reportedly targeted twice in Séno province. Military forces summarily executed 27 civilians, most of whom were Fulani.*

Despite rampant documentation of Fulani targeting by the VDP and even the national defense forces, the ruling regime has not offered any recourse. The simultaneous targeting and conflation of violent extremists with the Fulani further reinforces the culture of violence endorsed throughout the crisis. According to one Fulani cattle herder, every day is filled with fear of the military and violent extremists, because “someone will just come and kill you.”*

Breakdown of Bilateral Negotiations

The escalation of violence is also rooted in the refusal to engage in alternative methods of securing peace and stability. Specifically, local-level, bilateral negotiations have previously provided localities a degree of relief from VEO-perpetrated violence. In the past, local leaders facilitated these talks with jihadists throughout their municipalities and at times were able to reach an agreement that was beneficial to both parties.*

Unfortunately, Traore’s regime has undertaken a zero-sum strategy and has forbidden any engagement with VEO actors. In December 2022, Traore announced “a total war” against terrorists,* with former Prime Minister Apollinaire Kyelem de Tambela reiterating in May 2023 that the regime will “never negotiate, either over Burkina Faso's territorial integrity or its sovereignty…The only negotiations that matter with these armed bandits are those taking place on the battlefield.”* The ruling junta’s position has all but eliminated local intervention in the conflict and has relegated community leaders to the sidelines as their localities are ravaged by VEOs and state forces.

Previous administrations were tolerant and even at times amenable to peace negotiations and open dialogue between community leaders and insurgent fighters.* During the military-led rule of Paul-Henri Damiba between January and September 2022, local dialogue committees were established across the nation, resulting in dozens of pacts where jihadists offered civilians greater freedom of movement in exchange for strict compliance to sharia law and eschewing support for the state or collaboration with its defense forces.* Although these peace talks did not result in the complete withdrawal of VEOs, the informal truces provided civilians with some reprieve—as one concession necessitated weapon-clad jihadists leave their weapons outside of towns and mosques.*

Without any framework that outlines concessions tied to the cessation of violence, VEO groups are not beholden to any moral grounding in their offensive. Furthermore, absent state approval of community sponsored dialogues, local leaders are unable to negotiate, much less engage with insurgents familiar with the bureaucracy of peace agreements. Lacking state support or acknowledgement, VEOs may view local-level agreements as disadvantageous, as it would reduce their area of control and undermine their identity as a legitimate threat to the state.* Threatening VEO legitimacy is highly risky as VEOs are prone to carrying out retaliatory attacks on villages expected of aligning or cooperating with the state. At times, targeting is more arbitrary, and VEOs ambush villages due to their proximity to locations where state forces conducted operations resulting in VEO fatalities.* While insurgents may engage with the public, they also undertake actions that intimidate civilians and coerce compliance to their movement. VEOs will continue to target civilians to serve political and military objectives. By targeting civilians, insurgents exhaust communities into either providing support for their movement, or at least withholding support for the state.

According to reports, negotiations were mainly localized and offered results that were contained within the contested area. However, localized dialogues create clear cut transactions. Community leaders navigate and vocalize the immediate needs of their municipalities outside of the impersonal objectives touted by state-level recovery programs. Scholars at the International Crisis Group think tank assert that local-level negotiations help offset social tensions, prevent the perpetuation of hate speech targeted at the Fulani, and protect certain communities from retaliatory jihadist attacks.* Local-level negotiations offer bespoke resolutions to complex social and economic dynamics not always understood by state-level officials and their respective personnel.

Integrating local-level narratives into the counterterrorism repertoire further humanizes the conflict. Awareness of on-the-ground realities and the immediate dangers threatening localities could prevent catastrophic high-casualty events carried out by VEOs and state-supported militias. Reports of VDP abuse should also be taken seriously and lead to the demobilization of specific units when flagged by community members.* According to the New Humanitarian, dialogues further address political and socioeconomic grievances shared by the public and local jihadists *

One leader noted the end of bilateral talks “has greatly increased the crisis, because when so many people [were talking to jihadists] there was hope for peace.”*The length of the conflict has necessitated negotiating “in one way or another an agreement with the men of the bush,” activating social ties that allow for greater trust between the two parties in future discussions. Negotiating with jihadists is far from ideal, but the outlawing of local-level discussion has instilled the public with “great distrust” towards the government. Public fear stems from the severe repercussions associated with supporting or collaborating with jihadists. Even accusations inspire fear of retribution.* However, as civilians are forced to coexist with jihadists, it is uncertain how exact undiscerning militias will be in their targeting of jihadists dispersed throughout mixed communities.

Stuck in the Past: VDP Strategy Remains Stagnant as VEOs Expand

Rather than restructuring the VDP to offset growing violence and fatalities, the ruling junta has doubled up on its commitment to advancing the VDP and its mission. However, as the VDP continues to grow, their overall strategy has remained relatively stagnant. Although they are deployed throughout most of the country, the VDP have created security gaps wherever they are stationed. The VDP has been defined by unclear objectives, questionable command structures, and disorganized operations—a far cry from VEOs known for tailored operations and clearly defined hierarchies.

As official affiliates of the transnational networks of al-Qaeda and ISIS, JNIM, ISWAP, and IS Sahel have access to funds, equipment, training, and forces that have been finetuned and specialized over the decades. Lulls in violence might not suggest increased VDP efficacy but might instead mean the reorganization and recalibration of tactics to secure quick victories against state forces and the eventual takeover of the region.

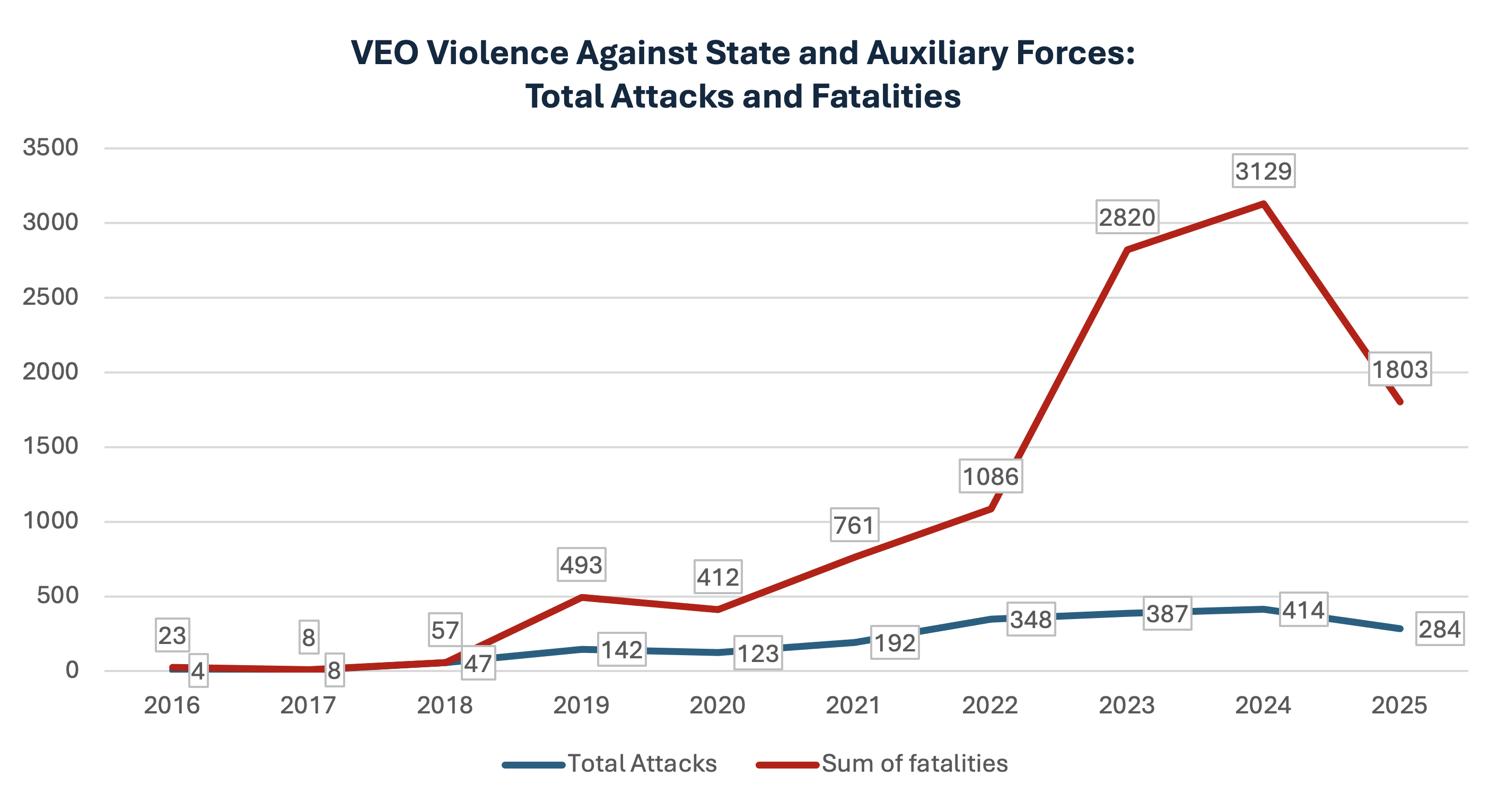

It is worth examining how significantly VEO attacks against state and PGM forces have increased during the conflict. The shift in lethality occurred not at the deployment of PGMs but following the first high-casualty attack targeting suspected jihadists. In January 2019, the Kogleweogo ethnic militia—prior to VDP formation—carried out one particularly lethal attack against a community of suspected jihadists. Over 220 civilians were killed.* The targeted attack against suspected VEOs likely launched a renewed effort by burgeoning VEO cells to launch aggressive campaigns against the state and its affiliates. These tit-for-tat attacks have grown exponentially more deadly.

Search results limited to “Battles” as “Event Type.” Timeframe inclusive of January 1, 2015 through June 4, 2025. VEOs include: Ansarul Islam, Islamic State in the Greater Sahara (ISGS), Al Mourabitoune Battalion, JNIM: Group for Support of Islam and Muslims, Islamic State West Africa Province (ISWAP) - Greater Sahara Faction, Islamic State Sahel Province (ISSP). State forces include: VDP, Military forces of Burkina Faso—including presidential unit and special forces units, Police forces of Burkina Faso, Koglweogo Militia, and Dozo communal militia.

Notably, battles increased from a total of 47 in 2018 to 142 in 2019. Interestingly, battles decreased from 142 in 2019 to 123 in 2020 following the state sponsorship of the VDP. However, it is possible the decrease could be due to how much VEOs considered VDPs to be a threat. Initially, VDP recruits were mostly redeployed elements of the Koglweogo militias.82 Given that they were not an entirely new defense unit, the VDP potentially did not represent as significant of an additional threat to VEOs, resulting in somewhat stable battle levels. However, following large-scale recruitment drives in October 2022 and February 2023 that sought to increase VDP troop size by 50,000 and 5,000 respectively, VEOs significantly increased the number of battles against state forces and their proxy militias. In 2022, battles more than doubled from 192 in 2021 to 348. By 2023, battles slightly increased to 387, however, fatalities exponentially increased to 2820, more than double the 1086 fatalities observed in 2022. Even with a small increase in attacks—414 attacks or 27 more than the previous year—2024 was the bloodiest year in the conflict’s history, with 3129 fatalities.

|

Quarter 2025 |

VEO Attacks on State Forces/Militias |

Total Fatalities |

|---|---|---|

|

Quarter 1 |

167 |

945 |

|

Jan |

46 |

271 |

|

Feb |

62 |

299 |

|

Mar |

57 |

375 |

|

Quarter 2 |

117 |

880 |

|

Apr |

61 |

321 |

|

May |

56 |

537 |

|

Grand Total |

284 |

1803 |

Between January 1 and June 4, 2025, there have been a total of 284 attacks resulting in 1803 fatalities. Expectedly, following the announcement for an additional 14,000 VDP recruits in March 2025,* March saw the largest increase in violent attacks against state forces. Despite five less attacks in February, fatalities increased by more than 70 in March. While April reported similar figures to March, May saw a proportional increase in the number of fatalities to attacks carried out, with five less attacks than April but 216 more fatalities suggesting increasing brutality in VEO operations.

Dwindling State Support and JNIM’s Expansion

Throughout the conflict, JNIM has regularly been the most lethal group, with a history of altering attack strategies in changing security environments. Part of the group’s resilience is owed to a collaborative chain of command and the prioritization of local engagement. In comparison to civilian-led militias and their national counterparts, JNIM is a highly structured top-down hierarchy. Subgroups are also afforded the agency to navigate local conditions and environments to facilitate a JNIM takeover. Unlike units across Burkina Faso’s defense system, JNIM prioritizes local contexts and has engaged with community governance structures to better position themselves as a legitimate and more reliable alternative to the state.*

The 2022 acquisition of Turkish drones has provided Burkinabe military forces with a slight advantage against JNIM and other VEOs, as they can target larger or more difficult-to-access regions. The drones used in these operations—a tactical unmanned aerial vehicle called Bayraktar TB2—are known for their affordability and their precision air-strike capabilities and can carry up to four laser-guided bombs.* However, the military has excessively relied on the drones, to the point of rendering precision targeting null and void. Indiscriminate violence has escalated due to aggressive air campaigns, and civilians are often the collateral damage in clumsy operations intending to target violent extremists. In August and September of 2023, Human Rights Watch recorded two airstrikes on a busy market and a funeral that ultimately killed more than 50 civilians. Although a JNIM presence had been recorded throughout the targeted areas, eyewitnesses claimed JNIM fighters were not present during both drone strikes and even offered medical support to those injured post-strike.* Notably, civilian casualties were not referenced when the junta-run media announced the successful targeting of Islamist elements in both airstrikes. This flagrant dismissal of civilian lives has left the public disillusioned, with one survivor of the attacks stating, “no authority came to visit us. They consider us terrorists. … More and more, we lose hope of seeing the state coming back [here]. With such an abuse, our disappointment is complete. … If they had targeted terrorists, we could understand, but they targeted a crowded market with many civilians.”*

To offset increasing drone strikes and prevent government encroachment on areas under jihadist influence, VEOs increasingly rely on remote violence, and in JNIM’s case, suicide attacks are sometimes coupled with larger operations on military positions. Some of these tactics include improvised explosive devices (IEDs), landmines, mortar, and rocket fire.* Passive attack methods via IEDs along roadsides have killed hundreds of VDP members.* Violent extremists have been strategic and learned to change their attack strategies to successfully overwhelm these forces. Abandoning direct confrontations, JNIM uses ambushes and mine warfare to overtake underequipped and less capable civilian counterterrorism units.*

As state counterterrorism units have been unable to provide sustainable, long-term protection, JNIM has asserted control over significant areas in northwestern Burkina Faso, including rural portions in the Nord and Boucle du Mouhoun regions. Eastern Burkina Faso has also seen JNIM expansion.* Without significant state protection, these rural and neglected communities easily fall under the influence of JNIM. Through their unofficial takeover, JNIM can easily impose blockades on critical transit corridors, tax civilians for revenue, restrict civilian movement, and even close schools.* It should also be noted that JNIM and IS Sahel are equally willing to strategically destroy necessary state services and infrastructure, such as supply routes and communications systems; and have targeted NGO convoys and UN peacekeepers to force civilian reliance on VEO-supervised provisions and services.*

The erosion of public trust towards the state has proved beneficial to JNIM’s propaganda and recruitment tactics...

JNIM undertakes the strategic initiative of strengthening social ties between their movement and the communities under their control. The erosion of public trust towards the state has proved beneficial to JNIM’s propaganda and recruitment tactics as the state consistently disappoints the public in ensuring their safety against violent actors. According to a report published by the United Nations Security Council in February 2025, JNIM has also increased its recruitment based beyond the Fulani and the Tuareg. By extending their outreach to the Bambara and ingratiating themselves with the ethnic community, JNIM increases their support network and further asserts their status as the leading authority for locals across the country.*

What’s Next?

According to civilians, the conflict is far from clear cut and “no one knows who’s who any longer.”* The crisis has reached a crossroads as actors on both sides of the conflict engage in unpredictable and lethal levels of violence against civilians. Effective security engagement is dependent on how much the public trusts defense agents; however, Burkinabe forces face a long road ahead in reassuring local communities of their objectives. Civilian-led militias and national defense forces have carried out unspeakable acts of violence against scores of innocent civilians and have not offered any source of reprieve for affected communities. Community-led and state forces have put themselves in a precarious position by being dismissive of civilians and their fear for safety, as a worn-down public can only remain compliant for so long.

As the state champions a security structure independent of governance or law and order, civilians may choose to redirect their support away from the government and actively oppose the regime. Worryingly, widespread public resentment led to the success of the first military coup in January 2022. Resentment also fed the flames of public demands for the removal of French and Western forces who were unable to significantly offset the ongoing violence carried out by increasingly growing and often more fatal terror groups. A disillusioned public coupled with opportunistic coup leaders exploiting the anti-West narrative ultimately resulted in unbridled support for Russia. The Kremlin-backed private military company BEAR was deployed in May 2024; however, they were not enlisted as counterterrorism support. Rather, BEAR is a designated protective force for the coup government.* As the coup government hoards security forces for their benefit, they are continuing to deny Burkinabes the right to safety and protection. However, if the past proves anything, when the public’s demands are not met, an unwavering movement of resentment can fuel generations of political instability.

Accordingly, marginalized communities are key targets for VEOs who prey on their second-class social status as justification to radically oppose and take down a corrupt regime. As the state’s military forces and auxiliary units continue to prioritize brutal and indiscriminate counterterrorism operations, the public grows more disillusioned with every new summary killing and forced displacement. The legitimacy of the state is hanging by a thread and the failure to contain jihadist activity despite employing record levels of violence further compromises public confidence in the state’s so-called counterterrorism program. Burkina Faso’s counterterrorism network has in fact become so bloated that another significant challenge will arise well before violent extremism is completely, if ever, eliminated. Demilitarizing the VDP’s projected 100,000 units will be no easy feat and if not approached effectively, will leave the country vulnerable to another cycle of having to contain large arms-trained groups.

Increase in VEO Recruitment

The severity of the direct targeting of the Fulani has provided VEOs a persuasive angle in ensuring support from this oppressed demographic. By examining the consequences of unchecked and unaccountable PGM activity on marginalized groups, specifically the Fulani, these administrative deficits provide VEOs, particularly JNIM and IS Sahel, with a blueprint of narratives to promise civilians when seeking their loyalty. According to the United Nations, JNIM has mastered this approach in securing public support and even recruits in order to legitimize their position of authority within the conflict.*

International Alert exposed that young Fulani in the Sahel expressed “a complete lack of trust among the communities in the defence and security forces.”* It is difficult to instill confidence in the objectives of the country’s defense forces as the VDP’s recruitment efforts overlook the Fulani, and Burkinabe counterterrorism operations continue to fatally target Fulani communities. As Burkinabe defense practices prioritize an anti-Fulani agenda over protecting this already marginalized group, the state has demonstrated approval of security response that is nothing if not considered crimes against humanity.

According to the United Nations, indiscriminate violence justified as legitimate counterterrorism policy quickly becomes an “accelerator of recruitment by radicalized groups and militias.”* The violence perpetuated by these defense units creates a successful tool of passive recruitment for insurgents. The horror of living through violent experiences and seeing no justice for these crimes has greatly motivated civilian conversion to the insurgency. Without an accountable government, targeted communities are given reasons to rebel against the state and align with violent extremists who claim to offer security and protection. Granted, some individuals might join VEOs not for their hardline religious goals, but for the opportunity to retaliate against a negligent and corrupt government. Interviews with Fulani leaders reiterate these reasons of long-awaited retribution.*

A 2023 survey published by the United Nations Development Programme (UNDP), found that 71 percent of around 300 VE recruits claimed that the trigger event that motivated them to join a VE group involved government action in killing and arresting their family or friends. After experiencing events inducing significant feelings of anger and fear, potential recruits are expected to join VEOs quickly.* Accordingly, post trigger-events, 62 percent of 550 respondents joined VEOs to seek recourse.* Those who joined were also more likely to get others to enlist, as 90 percent of 69 respondents recruited others after they joined the movement.*

Feelings of retaliation and revenge run deep across communities affected by state violence, and although guilty of egregious acts of violence themselves, JNIM’s leader has previously issued apologies for killing civilians,* showcasing a level of accountability that has so far been absent from the government. To restore the authority of the state and ensure the safety of civilians, Burkinabe authorities will have to drastically shift their commitment to delivering justice to civilians. Currently, the levels of indiscriminate violence with impunity have pushed civilians to the edge, leaving some of them questioning the purpose of the state’s justice sector if it does not check the agendas and motivations of the state’s defense sector.

Further Deligitimization of the State

However, PGM violence against civilians carries significant risks of further delegitimizing the state as it not only demonstrates a lack of commitment to civilian safety—one of the drivers of violent extremism*—but it also signals that the state is incompetent or unwilling to accurately identify and contain VEOs.* The inadequate delivery of security and justice further compromises civilian loyalty to the state, and enhances the legitimacy of VEOs.

Negligible oversight mechanisms exist or investigations are not actively carried out to ensure contractors follow rules of engagement and comply with the laws of war.* Subsequent acts of civilian-targeted violence have either been outright denied by the state. Investigations were launched into Koglweogo attacks in 2018 and 2019, but little progress had been made in furthering the cases by 2025.* This unchecked autonomy allows PGMs to evade legitimate channels of punishment for grave crimes, further catalyzing civilian resentment of the state. Without any credible monitoring and legislative channels to hold transgressive troops accountable for their inhumane actions, civilian troops are given judicial leeway in how they conduct their, and not the state’s, counterinsurgency agenda.

State legitimacy requires more than protecting civilians. Effective systems of governance also integrate developmental goals into their policies to ensure sustainable safety. However, according to regional scholars, Sahelian coup leaders have prioritized protecting the capital and have since abandoned goals of reclaiming and stabilizing rural areas. These areas are the most vulnerable to VEO control and even if the state has pushed VEOs out, they are likely to return when state forces depart.* As the state continues to divide civilians along lines of arbitrary importance, entire communities will be isolated and grow resentful of how quickly the state abandons its citizens during critical periods of instability.

Complications Surround Demilitarization of VDP

Whenever the VDP’s deployment ends, the Burkinabe government faces another long-term obstacle. Almost 100,000 VDP troops will have to be demobilized and reintegrated back into society. Safely assimilating VDP troops back into their communities will require explicit protocol that leaves no room for interpretation as it is expected some units will resist the return to civilian status. As the VDP has become synonymous with heavy defense and unpredictable targeting, demilitarizing VDP forces will require more than seizing weapons and uniforms once their deployment is completed. Demilitarizing the VDP also requires ensuring those currently deployed are not perpetuating the culture of violence that has consumed the force. By regularly castigating unnecessary violence across counterterrorism operations, the VDP and state forces could potentially better understand that the end of their campaign is a necessary component, and overall goal, of effective counterterrorism.

Ideally, the addition of the Fulani into the VDP could encourage true counterterrorism directives of collective security rather than militarized ethnic division. However, long-standing prejudices are not always easy to reform and sometimes require generations of unlearning to legitimately dispel discriminatory narratives. While the Fulani may also be hesitant to join the ranks of a force that actively villainizes them, the gradual integration of Fulani into the VDP—possibly through minimum quotas per unit—could strengthen social cohesion. New VDP recruits could also be subject to approval by local committees, which would provide community members with greater control over their own security.

Strict recruitment guidelines and vetting policies could potentially prevent the VDP’s forces from being overfilled with power-seeking individuals. However, the enormous size of the VDP makes it almost impossible to ensure policy compliance when on-the-ground conduct regularly contradicts the legitimacy of counterterrorism operations. The VDP have proven to be a long-term challenge to overcome, but promptly delineating deactivation frameworks and increasing awareness of this process could reinforce public understanding and acceptance of VDP deployment as a short-term campaign to eliminate immediate threats rather than a permanent addition to Burkina Faso’s security structure.

Conclusion

The normalization of violence rampant throughout Burkina Faso’s defense sector sets a dangerous precedent for future counterterrorism operations across the Sahel. Hardline security-based crisis response offers limited room for alternative pathways to peace and stability.

Although unorthodox, the Burkinabe defense forces could adopt non-violent operational strategies used by VEOs—who to some degree have been successful in their resiliency throughout the conflict—by adopting clearer chains of command and facilitating intelligence sharing and constructive cooperation among the various lines of defense. The Burkinabe counterterrorism scheme could also benefit from greater integration of local narratives and prompt responses to on-the-ground grievances rather than perceived communal slights.

As the prospect of democracy becomes a more distant reality—coup leader Captain Ibrahim Traore dissolved the entire government in early December 2024*—the safety of millions of Burkinabe also remains in flux. Without rule of law and credible systems of governance, Burkina Faso will never get ahead of the crisis or remedy the negative externalities resulting from the deployment of what can only be described as the subsidiary force of a defense pyramid scheme.